Policy Papers

Skills-Training Reform in Ontario: Creating a Demand-Driven Training Ecosystem

Karen Myers, Kelly Pasolli and Simon Harding on Skills Development

Summary of Recommendations

1) Test, replicate and scale sector-focused training that builds on the SkillsAdvance Ontario pilot program to target skills-training to sectoral needs.

2) Explore the feasibility of Career Pathways including supporting Ontario post-secondary institutions to build stronger relationships with employment service providers and employers. This could take the form, for instance, of providing more flexible funding options that enable post-secondary institutions to offer shorter credential programs as well as invest in student support services and employer engagement capacity.

3) Build ecosystem for demand-informed models including supporting the creation of business-led training networks involving various stakeholders such as post-secondary institutions, employment service providers, employers, industry associations, and labour unions to design and deliver localized skills-training programming.

4) Adopt aspects of Australia’s model for more proactive employer engagement in order to better inform skills-training priorities and support the connection between employers and jobseekers.

5) Learn what works through outcome-based metrics with a particular focus on sustainable employment linkages.

Introduction

The world of work is changing. Changes in technology, demographics, and the environment are shaping the jobs of the future and the skills that workers will need to succeed in these jobs. While many early predictions about automation and mass layoffs were exaggerated, there is little doubt that the changing labour market is putting new pressures on Ontario’s employment and training system.

Is the system ready to meet these challenges? In this paper we argue that significant changes are needed to make Ontario’s employment and training system more flexible, responsive, and resilient to the future world of work. Our goal is to ensure that all Ontarians, including especially those most likely to be affected by technological changes and other disruptive trends, receive the support they need to navigate the changing world of work – while also making the system more responsive to the rapidly changing needs of employers and local economies. Meeting this goal will require active collaboration among employers, citizens, educational institutions, and governments. It will also require a system-wide approach that embraces experimentation, testing and a commitment to scaling what works.

The question of how to future-proof Ontario’s employment and training is particularly timely given that the provincial government is in the midst of a major transformation to its employment services. This transformation will have far-reaching implications for adults seeking career advice and guidance and provides an opportunity for new thinking on how to prepare Ontarians to thrive in the changing world of work.

Our paper is organized into four sections. We begin with some context on Ontario’s changing labour market and the pressures these changes are creating for our employment and training system. Next, we turn to the evidence base on skills development to identify approaches that could strengthen Ontario’s employment and training system. We specifically highlight sector-based training models, a demand-led, evidence-based approach to skills training that connects training with employer and labour market needs, as a promising strategy. We also highlight where we have knowledge gaps and need to experiment to learn what works. Following this, we analyze Ontario’s current state employment and training system to highlight strengths, gaps, and opportunities for change.

In the final section, we offer five recommendations for strengthening Ontario’s employment and training system. The recommendations focus on adapting, testing and scaling evidence-informed approaches to employment and training that will better equip workers, jobseekers and employers to meet the challenges of the future. Together our recommendations offer a blueprint for a more flexible, responsive, and forward-looking employment and training system that will prepare workers and employers in Ontario for the future of work.

Context

A changing labour market

Ontario will face significant labour market disruptions in the coming decades, driven by changes in technology, automation, and demographic shifts. The impacts of these disruptions are already being felt, with the closure of Oshawa’s General Motors plant being just one of many high-profile examples. Once one of the biggest auto assembly plants in the world, General Motors operated in Oshawa for 100 years, employing almost 23,000 workers at its peak. While that number has declined significantly over the recent decade, the upcoming loss of almost 3,000 jobs will still be a major blow to Oshawa’s economy. While GM has developed a forward-looking strategy to become home to a test track for autonomous vehicles, this strategy combined with a heroic effort to repurpose the assembly plant into a parts operation will still only save a few hundred jobs.

Of course, labour market disruption will not affect all regions in the same way. A combination of aging demographics and outmigration has already contributed to marked demographic and economic differences between urban and rural places. Populations are stagnant or even declining in many rural and remote areas. Employment, labour force participation, and income will likely continue to be lower than in urban areas. Recent analysis by the Brookfield Institute suggests that these gaps may deepen. As part of their Employment in 2030 project, they undertook an analysis of future skills needs in Ontario drawing on existing literature, consultations with stakeholders and labour market experts, and data analysis. Their findings suggest that Ontario’s industrial heartland – small manufacturing cities and towns in southwestern Ontario, which have already been hard hit – will be most susceptible to automation in the future. Their analysis also highlights other places such as Leamington and Norfolk, which have significant proportions of employment in agriculture, forestry, and fishing, as similarly vulnerable to further disruption.[1]

Labour market disruption will also affect workers differently. A large body of international research on returns to education has long pointed to differences educational attainment as a major source of divergent employment outcomes around the world.[2] Ontario fits the international pattern. The median annual earnings for Ontario workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher are nearly 50 percent higher than for their counterparts with just a high school diploma. Workers without postsecondary qualifications also fair poorly on other indicators such as the employment rate and labour force participation rate.

Moreover, while the participation rates of women without credentials have always been relatively low, recent analysis by Sean Speer suggests that we should be particularly concerned about the plight of working age men without postsecondary credentials. He presents striking data illustrating how this group has been, and will likely continue to be, particularly hard-hit by labour market changes. While Ontario’s overall labour force participation rate for the working-age population has remained steady, the participation rate for non-educated men has fallen by roughly 10 percentage points in Ontario since 2000.[3]

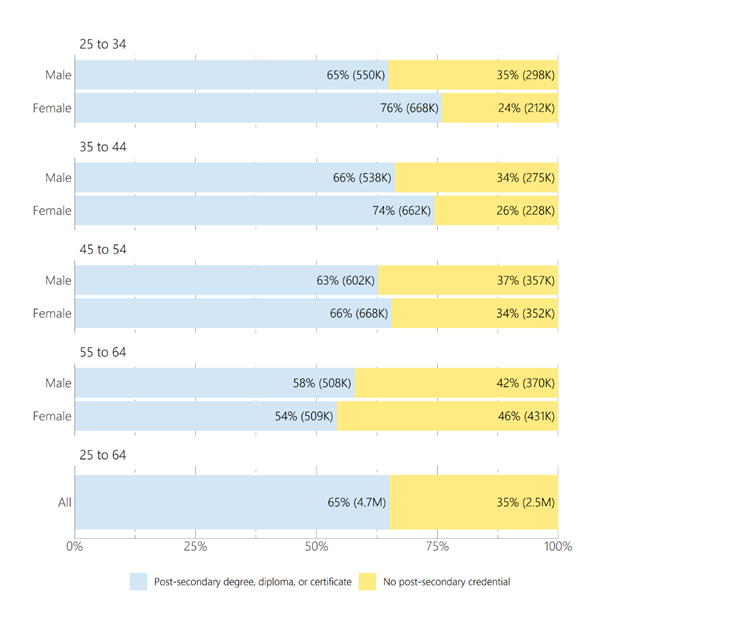

This growing gap matters. While Ontario is a leader in Canada and around the world in educational attainment, it is easy to forget that approximately 35 percent of Ontarians ages 25 to 64 – about 2.5 million Ontarians – do not have a post-secondary qualification (see Figure 1).[4] While younger cohorts are more likely than older cohorts to have qualifications, even among the 35 to 44 age group – a group that traditionally has had time to finish their initial education and establish themselves in the labour market – 34 percent of men and 25 percent of women in this age group do not have qualifications. Also note that as Figure 1 shows, males have lower post-secondary attainment in all age groups except for the 55-64 group.

Together, these changes will have significant implications for Ontario’s employment and training systems – creating both challenges and opportunities that should compel decision-makers to act. The remainder of the paper explores the evidence base on how to best to respond to these challenges and assesses the extent to Ontario is well-positioned to adapt and incorporate these practices into its ecosystem.

FIGURE 1 | EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT OF WORKING AGE ONTARIANS BY AGE GROUP AND SEX, CENSUS 2016 DATA[5]

Implications for Ontario’s employment and training system

Ontario’s labour market is already putting pressure on the employment and training system to be more responsive than the current system. New challenges will require a system that is much better able to support Ontarians in providing ongoing, flexible education and training in particular and navigating the changing labour market in general.

The importance of an employment and training system that supports lifelong learning has long been recognized in Canada.[6] But the changing labour market makes the stakes even higher.

While Canada is a leader in providing high-quality K-12 and postsecondary education, it has long been a laggard in workplace training and lifelong learning. Less than one-third of Canadians receive job-related, non-formal education. On average, working Canadians receive only 49 hours of job-related training per year, compared to an OECD average of 58 hours. Canada also spends 0.07 percent of GDP on training, well below the OECD average of 0.13 percent.[7]

There is also evidence that those who are most likely to need training are the least likely to receive it. People in rural and remote locations, those without postsecondary qualifications, and individuals with lower literacy levels, are less likely to participate in upskilling or reskilling opportunities.[8]

Greater and more effective investments in lifelong learning are needed to help Canadians prepare for the future world of work and help Ontarians in all regions, industries, and stages of their working life make informed career choices and access flexible, effective training options that will prepare them for jobs in in-demand sectors and occupations.

All of this raises the question of why has Canada not invested more heavily in job training? One possible explanation is that government sponsored training has gained a bad reputation for being ineffective and misaligned with employer needs. Indeed, this was the conclusion reached by Canadian economist Stephen Jones in his 2011 research paper commissioned by the Task Force on EI Reform. In this paper he argues that the returns to training for displaced workers are low and that on a cost-benefit basis, the body of evidence does not show that training pays off for most of the displaced population.[9] In the next section, we argue that while the evidence does suggest that training is not a panacea, the story on the effectiveness of skills training is actually more nuanced.

The evidence base

Does training work?

In an upcoming paper for the Institute for Research and Public Policy, we conduct a comprehensive review of the evidence on the effectiveness of training. The upshot of our analysis is that while some important and large-scale rigorous studies have found no impact for skills training, other rigorous studies have showed that training works (see Box 1 for selected examples in this body of evidence).

Taken together, studies from the US and Canada suggest that skills training is not a silver bullet, let alone a universally effective solution to displacement and unemployment. Rather, studies suggest a more nuanced picture: skills training can benefit certain groups, under specific conditions.

So what explains this variation? Simply put, not all training is created equal. The way training is designed and delivered matters, as does the context in which the training operates. Our analysis suggests that positive outcomes tend to be associated with two criteria. First, training should be aligned with the local labour market to prepare participants for employment in in-demand occupations. Second, training should align with the interests of the target population. Potential participants must see the target occupation as a good match for their skills and interests.

Getting skills training right is complex. Great care and attention are needed to design skills training programs that give workers the skills they need to obtain work that is both in-demand and a quality match. For practitioners and policy-makers, then, the most pressing question is how to foster training approaches that meet these criteria.

In this section we discuss two specific training strategies that have the potential to support Canadians on their lifelong learning journeys and ensure that training is aligned with labour market need:

- Sector-based models

- Career Pathways models

We review the evidence supporting the effectiveness of these models as well as the findings and lessons learned about how to successfully implement them.

Sector-based models: aligning training with labour market needs

As early as the 1980s, workforce practitioners in the US began to ask the question of whether working more closely with employers could make training programs more effective. This experimentation gave rise to sector-based training models. These models focus on delivering training that enables workers to transition into in-demand jobs in growth sectors and/or make career progress within these sectors.

Sector-based models emerged out of the insight that if training is more carefully tailored to existing jobs, the trainees will have much better chances of obtaining them. If employers were satisfied with these trainees, they would in turn be more likely to hire from the training program in the future.[10]

Building on this insight, workforce practitioners began to experiment with a “dual customer” approach in which employers as well as workers are considered to be clients. Practitioners focused on specific industry sectors so that they could develop deep industry expertise and better understand employer needs. Working closely with employers and industry associations ensured that candidates built the right skills to succeed in in-demand jobs, and obtain the credentials and licensing necessary.

Sector-based models generally require coordination with multiple partners including employers, industry associations, workforce boards and training providers. Some sector-based models rely on an intermediary organization or training broker who recruits industry partners, identifies skills needs, develops training programs, and oversees the recruitment, training and placement of participants.

Sector-based models were first used in the health and elderly care sectors in the US in the 1980s, but have since been used in a variety of sectors, including IT, manufacturing, construction, transport and logistics.[i] The model has been used to train disadvantaged adults and youth, as well as workers dislocated from previous jobs. The models have been implemented most widely in the US and embraced by state and local governments across the country.

Sector-based models hold great appeal in the context of the changing world of work. As skills needs and labour market demands rapidly shift, employment and training providers will need to work more closely with employers to understand and respond to these shifts.

Evidence for sector-based models

Multiple rigorous studies have found that sector-based training can have positive impacts on participant employment and earnings.

One of the most significant investigations into the effectiveness of sector-based models is the WorkAdvance Demonstration. WorkAdvance is a sector-focused model with a specific focus on career advancement. The model is currently being implemented by four providers across the US and is being evaluated using a randomized controlled trial design with over 2,500 study participants for a five-year follow-up period. At the three-year follow-up point, program participants earned 12 percent more on average than workers in a control group who did not participate in WorkAdvance, which translates to an additional $1,865 (USD) in earnings per year.[11]

The impacts of WorkAdvance for the long-term unemployed were larger than average. For these workers, WorkAdvance increased earnings by 14 percent, or about $1,930 (USD) per year.

WorkAdvance is not the only rigorous study of sector-based training that has shown positive impacts on employment and earnings. The Sectoral Employment Impact Study, a randomized controlled trial study evaluating three sector-focused programs across the US, found that the earnings of program participants were 29 percent higher than the control group, translating to about $4,500 more in earnings.[12]

Michaelides et al. summarized results from evaluations of three sector-based models in Ohio that focused on healthcare, manufacturing, and construction. The quasi-experimental evaluation found that all three programs were effective in helping graduates obtain employment a year after training completion.[13]

Implementing sector-based models

Sector-based models are not without their challenges. While several experiments have demonstrated positive results, the effectiveness has not been uniform. Even within the WorkAdvance study, there was variation in the degree to which different sites produced positive impacts for participants.

Evidence suggests four factors are important to the successful implementation of sector-based models:

- Understanding of employer needs – A thorough understanding of current and future skills needs is key to success. The demand for skills must be sufficiently strong relative to supply to justify training; likewise, efforts are required to identify emerging skills needs.

- Understanding of worker needs – Sector-based models must consider not only the “demand side” context but the “supply side” context as well – the current state of training programs, stakeholder interests, and whether there is a sufficient supply of interested, suitable participants who could not already access similar training through other means.

- Relationships and ecosystem dynamics – Collaboration and close relationships between employers, training providers, and intermediaries are a critical success factor. These relationships are local, context-dependent, and time-consuming to develop. This means a sector-based model may require several years of development before becoming successful.[14]

- Agility and labour market dynamics – Shifts in local labour market conditions that affect particular industries or occupations can impact the effectiveness of sector-based training models. Sector-based programs must have a strong, forward-looking understanding of labour market conditions and the flexibility and agility to adapt to sudden shifts, to be successful.

Career Pathways: creating accessible lifelong learning pathways

As sector-based models have spread across the United States, practitioners have begun to experiment with variants of the model that incorporate new partners and types of training. One model that has gained prominence since the 1990s is the Career Pathways model.

Like other sector-based models, Career Pathways is focused on preparing individuals for in-demand jobs. The model focuses specifically on aligning post-secondary training with labour market need by organizing training into a series of modular steps that align with successively higher credential and employment opportunities.

Career Pathways programs often seek to provide “on and off ramps” between the labour market and educational institutions at various points along the pathway, to meet the needs of both younger and older students and workers, including those who are either disadvantaged or dislocated from earlier jobs.

Like other sector-based models, Career Pathways requires the active engagement of employers to succeed. Employer input helps ensure that training and credentials align with specific, in-demand employment opportunities. The modular nature of the approach means that training can be more easily adapted to respond to changing skills needs, and is more accessible to adult learners seeking access to quality training at different stages in their career.

The Career Pathways model has been widely adopted in the US across multiple levels of government. The US federal government has recently institutionalized the approach by integrating a funding framework for the model into the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. A number of states, including California, Washington, Oregon, and Kentucky (ACTE 2019), have developed their own Career Pathways approaches, as have numerous cities (New York, St. Louis, and San Diego) and training providers, such as colleges and industry organizations.

Evidence for Career Pathways

Two large-scale demonstration projects in the US are studying the impacts of Career Pathways: Pathways for Advancing Careers and Education (PACE) and Health Profession Opportunity Grants (HPOG).

The PACE project is evaluating nine Career Pathways projects using a randomized controlled trial design. Thirty-month evaluation results were published in 2019 and reported promising impacts on educational attainment and earnings. One of the projects, the Year Up program, found that programs experienced a 53 percent gain in initial earnings over the control group, and a 40 percent gain at two-year follow-up. These are the largest earnings gains to date for workforce development programs tested with a randomized controlled trial.[15]

The HPOG project studied the impact of Career Pathways models in the health care sector, using a randomized controlled trial design. The evaluation found that the treatment group was more than 27 percent more likely to be employed in the health care sector, compared to the control group, and earned 4 percent more in the fifth quarter following enrollment.[16]

Implementing Career Pathways

The successful implementation of Career Pathways models requires effective employer engagement and the development of productive relationships and partnerships between employers, employment services and postsecondary institutions. Other factors that are important for the successful implementation of Career Pathways include:

- Ensuring sustainable funding – Establishing a sustainable funding model for Career Pathways can be difficult, as many programs have struggled to find ongoing resources to support different elements of the program including financial supports and support services for students.

- Recruitment – Many Career Pathways programs have struggled with identifying students who are a good fit for the specific sectors and occupations targeted, and have identified building stronger partnerships with referral partners and testing new recruitment methods as potential solutions.

Ontario’s employment and training system

It is clear that Ontario’s employment and training system is being confronted by major changes and will continue to be so in the future. How ready is this system to respond to the changing world of work?

About the system

Ontario’s major employment and training program is Employment Ontario, which encompasses a wide range of employment and training services funded by the province, including:

- Employment Service – offers a suite of resources, supports and services to support individuals to meet the career and employment needs of individuals and the labour needs of employers

- Literacy and Basic Skills – provides training in literacy, numeracy and other essential skills for adult learners

- Youth Job Connection – provides pre-employment training, job matching, work placements, mentorship and transition supports for youth experiencing multiple and/or complex barriers to employment

- Second Career – provides financial support for adult learners who have been laid off to pursue skills training

- Canada-Ontario Job Grant – provides financial support to individual employers or employer consortia who wish to purchase training for their employees

- Pre-apprenticeship – helps potential entrants to the apprenticeship system develop job skills and trade readiness

Table 1 presents information on government spending for each of these services in the 2015-16 fiscal year.[17]

Table 1 | Government Spending and clients served, by Employment Ontario service type, FY2015/16

| Service type | Total spending

($ millions) |

| Employment Service | 335.2 |

| Literacy and Basic Skills | 85.7 |

| Youth Job Connection | 42.6 |

| Second Career | 159.1 |

| Canada-Ontario Job Grant | 64.7 |

| Pre-apprenticeship | 13.6 |

Ontario also has a large network of postsecondary institutions including 24 publicly-funded colleges and 22 universities (20 of which receive public funding).

Ontario also has 26 Workforce Planning Boards in regions across the province. These boards are non-profit organizations that bring together local stakeholders, gather information about labour supply and demand, and coordinate community responses to labour market issues and needs. Ontario has also piloted the expansion of eight boards to become Local Employment Planning Councils, with an additional mandate to improve local labour market data, and to select and fund innovative projects that address local labour market issues.

Employment services transformation

In early 2019 the Ontario government announced a plan to transform the province’s employment services. The key features of the transformation include:

a) Integrating employment support services for Ontario Works and the Ontario Disability Support Program into Employment Ontario to create one system of employment service

b) Introducing service system managers responsible for managing employment services in each service catchment area, selected through a competitive process

The selection of service system managers for an initial prototype phase is already underway. The transformation is designed to support the government’s vision of a more locally responsive, outcomes-focused and client-centered system that will in turn achieve positive outcomes for both jobseekers and employers.

Gaps and challenges

Despite a chorus of voices advocating for more future-oriented approaches to employment services and training, Ontario’s employment and training system remains firmly rooted in the past. The foundation of this system is the Employment Service, which provides general career advice, job search assistance, and referrals to training programs. Training – particularly training that is responsive, demand-informed and focused on the skills needs of the future – is not a prominent feature of Ontario’s system.

To what extent does the transformation currently underway in Ontario’s employment services system provide an opportunity to reorient towards the future? The transformation is designed to support the government’s vision of an integrated, outcomes-focused and client-centered system. These goals are core to the mandate of any publicly funded employment service and align with a trend towards integration that began in other jurisdictions decades ago. While this alignment is to be applauded, we also note a striking absence of any discussion of how the new system will adapt to the dramatic changes in the labour market that are already occurring. The discussion of the transformation includes little reference to:

- Helping new segments of workers – As the labour market changes, employment services will need to serve not just the long-term unemployed and those facing barriers to the labour market, but workers affected by labour market disruptions and technological change.

- Proactively addressing labour market change – Rapid and unpredictable changes to the labour market will require employment services to be more proactive in recognizing and preparing Ontario to navigate these changes, rather than waiting until clients have already been negatively impacted to act.

The Ontario transformation provides a marked contrast to the recent employment services transformation in Australia which is introducing a new, digital-driven model to better adapt to the future world of work (see Box 2 for more information).

There have also been limited efforts to adapt Ontario’s training programs to increase their resilience and responsiveness to the future world of work. An initiative to modernize the Literacy and Basic Skills program was recently put on hold. The Canada-Ontario Job Grant has been adapted to make training more accessible for employers, but there remain gaps in the availability and quality of training that meet employer needs. A recent review of the Job Grant program found that the program was administratively onerous and that a significant proportion of funds were used to support training that employers were already willing to pay for themselves.[18]

Postsecondary education, for the most part, continues to follow a traditional format where students complete courses towards a two-year diploma or a four-year degree. This system can create barriers to access and lacks the flexibility to support the lifelong learning needs of workers who are trying to navigate the changing labour market.

Strengths to build on

Despite these challenges, Ontario’s employment and training system delivers benefits for many jobseekers, workers and businesses, and the system contains many important elements to build on. Ontario has also recently experimented with innovative and evidence-informed models that provide a strong foundation for future investments in programs and services that will help Ontarians prepare for the future world of work:

SkillsAdvance Ontario pilot

Ontario has already begun to experiment with sector-based training models through the SkillsAdvance Ontario pilot. The pilot funds projects that support jobseekers with sector-specific employment and training services and helps employers recruit and advance workers with the right skills. The pilot has funded initiatives like Tourism Skillnet Ontario, which brings together stakeholders in the tourism and hospitality industries to identify recruitment and training needs and align training with those needs.

Career Pathways pilot

The Ontario government, through the Ontario Centre for Workforce Innovation, supported a Career Pathways pilot project to test the feasibility of the Career Pathways approach in Ontario. The pilot explored the successes, challenges and lessons learned from implementing two programs that provide an initial “step” in a career pathway. The programs focused on building the academic and workplace skills that learners needed for entry-level employment in in-demand sectors while also providing a bridge to more advanced college credentials and employment opportunities.

Moving forward

We offer five recommendations for modernizing and future-proofing Ontario’s employment and training system.

1. Test, replicate and scale sector-focused training

The SkillsAdvance Ontario pilot is an important step forward in shifting Ontario’s employment and training system to be more demand-informed. Ontario should continue to support SkillsAdvance Ontario projects that provide workers with sector-specific employment and training services and help employers recruit and retain the talent they need.

As a precondition to scaling SkillsAdvance across the province, Ontario should evaluate the effectiveness of existing models. Models that demonstrate promising results should be replicated in new regions across the province. Ontario should also work with employers and other stakeholders to identify new industry sectors where a sector-based model could add value. As Ontario pursues both replication of models in existing sectors and expansion to new sectors, it should remember the lessons learned in other jurisdictions and ensure that system actors have the time and resources they need to establish new partnerships, assess employer needs, and ensure alignment with current training offerings in the local community.

Building the capacity of a wide range of training providers will also be key to effectively scaling sector-focused approaches. Ontario should explore strategies for building the capacity of training partners including industry/sector councils, private sector trainers and non-profits, to design and deliver effective training that is aligned with employer needs. Regularly and systematically collecting feedback from employers and participants will be important for monitoring training quality and responding to issues and gaps.

2. Continue to explore the feasibility of Career Pathways

Building on findings from the earlier pilot, Ontario should develop and test additional iterations of the Career Pathways model in high-demand sectors and occupations. These new iterations should focus on strengthening the alignment between credentials and employment opportunities at each step in the pathway, and providing supports and services to help learners navigate transition points. In addition to replicating Career Pathways approaches developed in the previous pilot (health care and supply chain logistics), Ontario should work with employers, labour market experts and other stakeholders to identify additional sectors where a Career Pathways approach could add value. These new models should be evaluated over longer time periods to assess their impact on educational attainment and career progression.

Implementing new Career Pathways models will require fostering strong relationships between postsecondary institutions, employment service providers, and employers. Postsecondary institutions can work with employers to identify their needs and develop training and credentialing strategies that align with these needs, while employment service providers can play a key role in recruiting and offering ongoing support to participants.

Building on earlier findings from the pilot, Ontario should also explore the feasibility of strategic policy changes that could reduce barriers to adopting Career Pathways models, including more flexible funding options that allow postsecondary institutions to offer shorter credential programs as well as investments in student support services and employer engagement capacity within the postsecondary system.

Rigorous evaluation of these Career Pathways models will be critical for determining whether the model is effective in the Ontario context and for identifying additional success factors, challenges and lessons learned that can be used to increase the model’s effectiveness.

3. Invest in building system infrastructure for demand-informed approaches

A truly demand-informed training system will require more than just delivering sector-based and Career Pathways training programs. Implementing these approaches on a larger scale requires a solid ecosystem infrastructure that helps ensure that models are aligned with the local context and with participant and employer needs. The Ontario government should support the development of sector-based training networks across a broad range of sectors and occupations that bring together stakeholders to identify training needs and coordinate recruitment and delivery efforts.

These efforts can leverage existing features of the Ontario employment and training system as well as features of the employment services transformation. For example, the new Service System Managers introduced through the transformation will be well-positioned to work with sector-based organizations and other stakeholders to identify training needs in their local area and coordinate training opportunities that effectively and efficiently meet the needs of many businesses. This approach will encourage the development of regionally informed, sector-specific training models that are aligned with the needs of employers. Service System Managers will also be able to ensure that there are strong connections between employment services and training opportunities, ensuring that clients accessing the Employment Service are aware of and can easily access sector-based training opportunities that align with their needs and goals.

Ontario could also consider supporting business-led training networks, modelled after the Skillnet program in Ireland. Under this model, groups of employers organized by sector or geographically could apply to form a training network organization that would coordinate training activities (see Box 3 for more information on Skillnet).

4. Explore opportunities for innovation in employment services

Strengthening Ontario’s skills development ecosystem is essential. But as a stand-alone investment, its impact will be limited. To ensure we achieve better outcomes for both people and places, we need to purposefully link our investments in skills development directly to our investments in our employment services system. The transformation of Ontario’s employment services provides an opportunity to experiment with new approaches that can better align employment services with the labour market needs of the future.

Other jurisdictions, such as Australia, offer useful insights into how employment services can be adapted to better meet the labour market needs of the future. As the transformation moves through the prototype phase, the government should explore opportunities to foster local innovation in employment services that will help new segments of workers affected by labour market change and respond more proactively to employer needs.[19] This could include encouraging service system managers to test new approaches such as:

- Innovative service delivery approaches that enable providers to effectively serve jobseekers closer to the labour market with light touch, high quality digital services, along with more intensive in-person supports for those facing barriers

- Use of new technological tools and digital platforms that support skills assessment, job matching and employment navigation

- More proactive employer engagement to identify skills needs and ensure employers can quickly and easily access qualified candidates

5. Learn what works

As Ontario’s employment and training system moves forward, it will be critical to collect information on what’s working, what’s not working, and what lessons can be learned. A consistent, system-wide approach to monitoring and evaluating the results of employment and training programs will help identify which models are most effective and respond and react to changes over time.

An important part of this strategy will be leveraging administrative data to accurately and efficiently track long-term outcomes and estimate impacts. Linking provincial data holdings with federal data on long-term employment and earnings will enable Ontario to explore long-term effectiveness and accurately estimate the impacts of employment and training programs.

Ontario should also invest in rigorous evaluations of new employment and training models, such as SkillsAdvance Ontario and Career Pathways models, to identify success factors, challenges and lessons learned and to identify what models are most effective. These evaluations can help inform the design of “made-in-Ontario” approaches to skills training that draw on existing evidence but adapt models where needed to align with the Ontario context.

Dr. Karen Myers is the founder and leader of Blueprint, a non-profit organization dedicated to improving the social and economic well-being of Canadians by helping to solve complex public policy challenges. Blueprint is one of three partners leading the Future Skills Centre – a six-year initiative with a mission to develop and rigorously test new approaches to help Canadians develop the skills necessary to succeed in the new economy. The Centre is funded by the Government of Canada and led by a partnership between Ryerson University, the Conference Board of Canada and Blueprint. Blueprint is leading the Centre’s evidence generation strategy and the evaluation of the Centre’s projects. Over the past twenty years, Karen has built a solid reputation for her ability to lead large-scale, complex projects in a range of policy domains including employment and training, poverty reduction, income security, and housing affordability. She has extensive experience as a researcher, policy analyst, performance consultant and program evaluator that spans the public, private, and non-profit sectors. Prior to founding Blueprint, Karen was a research director at the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation and a senior policy advisor with the Ontario Government. She began her career with Benchmark Performance, a consulting firm focused on helping people and organizations deliver results. Karen holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Toronto and a Master of Public Administration from Queen’s University.

Kelly Pasolli is the Director of Policy and Program Design at Blueprint. She has experience leading a diverse range of projects including policy analysis, program design, the design of performance management, monitoring and evaluation frameworks, and evaluations of complex initiatives. Her work involves close collaboration with government and community organizations to develop responsive, evidence-informed policy solutions and to build and implement strategies for generating evidence about the performance of programs and initiatives. Kelly has worked in a wide range of policy areas including employment services, skills development, housing and homelessness and income security. Kelly holds a Master of Science in Political Science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Simon Harding is a Senior Researcher with Blueprint. He is an expert in research design and policy analysis, and is committed to identifying and measuring the impact of innovative solutions to pressing public policy challenges. He has experience working with a range of organizations to identify and implement evidence-informed solutions that increase the impact of their work Simon’s research and analysis has contributed to the development of evidence-informed solutions across a number of policy domains, including employment services, skills development and economic development. Simon holds a PhD in Resource Management and Environmental Studies from the University of British Columbia.