Policy Papers

Navigating Uncertainty in Ontario’s Budget

Sean Speer, Drew Fagan and Michael Cuenco outline best practices for budgeting in crisis, offering advice and insight for policymakers charged with planning the next Ontario budget, due in November.

Issue Statement

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted Ontario’s public health environment as well as its economy. The situation remains fluid. Government policies – including restrictions on business and household activities – continue to evolve as public health officials learn more about the virus, how it spreads, who it affects, and how best to treat it.

The combination of restricted economic output and general uncertainty has wrecked havoc on governmental budget planning. It has become highly challenging to project revenues and expenditures in such a complex and fast-moving environment. Several governments, including Ontario’s, opted to delay their 2020-21 budgets as a result.

The Ontario government is now committed to releasing a full, multi-year budget in November 2020. The challenge, of course, is that the pandemic continues to unfold and a second wave promises to cause yet more disruption. Ontario’s ministry of finance is now producing a 2020-21 budget in an environment of unprecedented uncertainty.

This policy paper draws on research and scholarship on public sector budgeting in a crisis to offer advice and insight on how best to craft and present the provincial budget in the context of persistent uncertainty.

The key takeaways for Ontario policymakers are to adopt substantive budgeting practices, including scenario planning and contingency budgeting, as part of the forthcoming budget, as well as to adopt communications strategies linked to such practices.

Decision Context

The Ontario government was required by law to table a multi-year budget by March 31, 2020. The province’s ministry of finance worked diligently in January and February to meet this deadline. Then the COVID-19 pandemic radically reshaped the public health and economic environment in mid-March. The budget’s underlying assumptions were overwhelmed. As a result, the government opted to shelve its multi-year budget and instead released a short-term fiscal update.

Finance Minister Rod Phillips committed at the time to table a multi-year budget in November 2020. It was ostensibly assumed that the public health and economic environment would have stabilized by then. But, in the intervening time, the circumstances have not markedly improved. There are growing concerns about rising cases in various parts of the province and the government has recently enacted a new round of business and household restrictions. The ministry must therefore produce a budget in a context that remains highly fluid. As we will outline below, the current level of uncertainty is among the highest ever recorded, according to various models.

It is useful to start by understanding how COVID-19 has impacted Ontario’s public finances. The pandemic has significantly reduced government revenues while driving up its short-term expenditures. This double whammy is sometimes described by economists and public finance experts as a “scissor effect.”[1] Consider that the revenue projections for 2020-21 have fallen by more than $10 billion in the year since the province’s Economic and Fiscal Outlook in November 2019 and expenditures have risen by roughly $20 billion. The net effect is that the 2020-21 deficit projection has climbed from $6.7 billion to $38.5 billion (see Table 1).

Table 1: Ontario Government’s 2020-21 Fiscal Projections from March 2019 Budget, November 2019 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, March 2020 Economic and Fiscal Outlook, and August 2020 Quarterly Update[2]

It now seems likely that the pandemic’s effects on public health and the economy will persist for some time. Although the Ontario government’s budgetary balance will likely start to improve next year, there is no question that its medium-term fiscal plan has been significantly altered. Not only has its deficit projection risen almost six-fold in 2020-21, but the deficit is also likely to continue beyond 2023-24 when the government had previously projected a budgetary surplus. This could have major implications for the provincial government’s credit rating and its long-term fiscal sustainability.

This challenging fiscal environment is dominated by uncertainty. Uncertainty is often perceived as a qualitative consideration. It is typically used to describe the fluidity of exogenous forces that can affect the economy, society, and government. But economists and other scholars have increasingly sought to treat uncertainty as a quantitative phenomenon. That is to say there are various methodologies for measuring uncertainty.

One of most cited is produced by a group of economists led by Northwestern University professor Steven Baker, Stanford University professor Nicholas Bloom, and University of Chicago professor Steven Davis. The Economic Policy Uncertainty Index uses newspaper-based analysis (based on a series of key words such as “economics”, “policy”, and “uncertainty”) to build an economic policy uncertainty index that tracks uncertainty over time across advanced economies.

The index is primarily intended to capture policy uncertainty – including, for instance, expiring tax policies. But it can also provide insight into general economic uncertainty. Baker and his co-authors have, for instance, used the index to estimate uncertainty in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. The index shows that global economic policy uncertainty has reached unprecedented levels in 2020.[3]

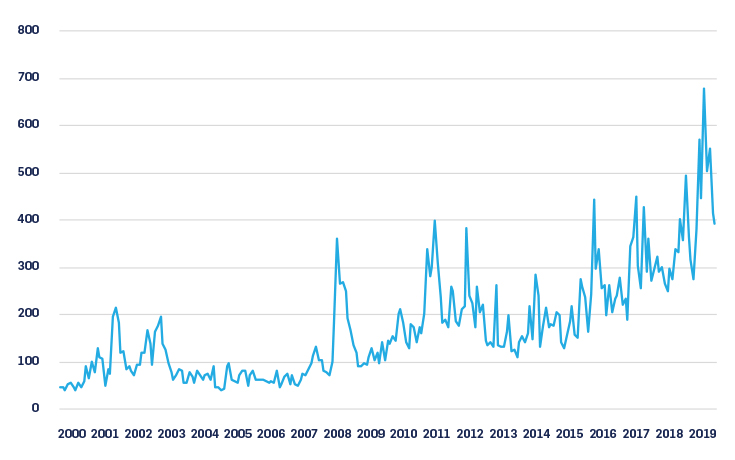

This applies to Canada as well. The economic policy uncertainty index (using the Baker, Bloom, and Davis newspaper-based methodology) shows that Canada’s level of uncertainty jumped by 50 percent in March 2020, peaked in May 2020, and remains elevated above pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Monthly Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, Canada, January 2000 to September 2020[4]

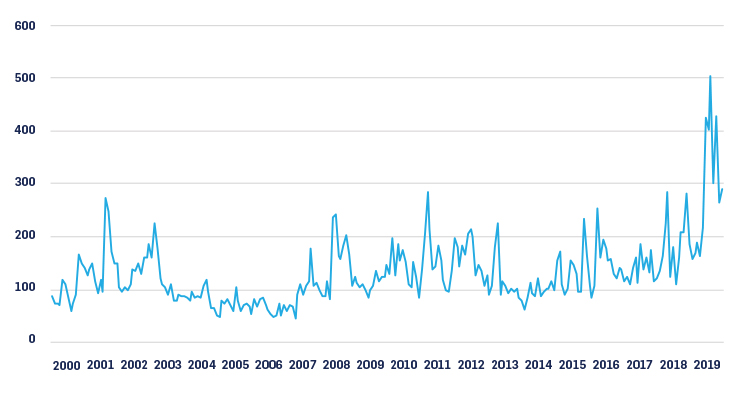

In fact, according to Baker, Bloom, and Davis’ analysis, Canada’s level of uncertainty has been elevated even relative to the United States over the past several months (see Figure 2). Setting aside the potential for methodological or cultural explanations for these differences, the main point here is that Ontario policymakers are facing unprecedented uncertainty as they develop the province’s budget.

Figure 2: Monthly Economic Policy Uncertainty Index, United States, January 2000 To September 2020[5]

Budget-making in an environment of heightened uncertainty is highly challenging. The basic inputs to a government budget are economic projections including real and nominal GDP growth, inflation, unemployment, and so on. These economic metrics are used to estimate revenues and expenditures. If there is a high degree of uncertainty embedded in these estimates, it can make it extremely challenging to produce reliable revenue and expenditure projections. Consider the revisions in Table 1. Within months, the government’s deficit projection has grown almost six-fold due to pandemic-induced changes to revenues and expenditures.

This, by the way, is a significant swing even relative to previous crises. Take the 2008-09 global financial crisis, for instance. Between the 2008 and 2009 budgets, the province’s projections for the 2009-10 fiscal year swung from a balanced budget to a $14.1 billion deficit due primarily to significant stimulus-related expenditures.[6] The year-end figures resulted in a $19.3 billion deficit which is nearly a four-fold increase relative to the 2008 budget.[7]

The main difference between the 2008-09 experience and the current one is the magnitude of revenue changes. The Ontario government was actually able to outperform its revenue projections in 2009-10 because the breadth of the recession was smaller and the recovery was relatively faster. It is unlikely that the government is going to experience much upside in its revenue projections this time around due to ongoing business restrictions and heightened uncertainty. It is quite possible, in fact, that revenues continue to lag as the economy operates at less than full capacity for the foreseeable future.

This point is worth emphasizing: as we have come to better understand the coronavirus, expectations of a V-shaped recovery have been replaced with an implicit recognition that the public health and economic conditions are unlikely to return to a pre-pandemic status until a vaccine is widely distributed. There is unlikely to be a major inflection point here. Instead we will continue to muddle along with the economy operating at less than full capacity for months or even years. This will have major consequences for provincial fiscal policy – including lower revenues, higher expenditures, and negative effects on childcare, public transit, education, health care, and so forth.

Our economic theories and models are not generally well-equipped to account for such a scenario. Policymakers will need to try to incorporate this unique set of conditions into budget planning, communications, and implementation.

The good news is that these challenges are not unique to the Ontario government. Governments around the world are facing similar challenges managing their budgets in the context of COVID-19. There is also considerable scholarship on budgeting in a crisis and how to effectively plan for uncertainty in fiscal policy development. Our goal here is to draw on this combination of research and practical experience to suggest ways that the Ontario government might navigate the uncertainty and manage risks to its budget projections.

Decision Considerations

As the Ontario government develops its multi-year budget, it should not try to downplay the level of uncertainty it is facing. It should instead lean into it. It should aim to incorporate uncertainty into the budget planning process. The goal should be to communicate the risks to the public and the markets, insulate against the potential of future shocks, and start to prepare for the post-pandemic recovery. Achieving these goals will require a combination of communications and presentational strategies as well as substantive budgeting practices.

What does the research tell us? Budgeting in a crisis should involve various elements.

Clear and credible budget communications

Being clear, accessible, and transparent about the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic can go a long way in setting expectations, informing public debate and shaping public reactions to government policy in constructive ways. A forthcoming Ontario 360 policy paper provides more general analysis and advice about the role of communications and framing in a crisis. But it is particularly important in the context of budgeting.

The International Monetary Fund has highlighted the importance of clarity and credibility in budget communications.[8] This is crucial for maintaining confidence in the government’s agenda and its capacity to address the ongoing and evolving challenges associated with the pandemic. The IMF identifies some specific components to effective budget-related communications, including:

- Catalogue previously and newly-announced pandemic-related measures including up-to-date details and costing: This is an opportunity to highlight take-up of previously-announced programs, possible design or implementation changes, and an overall picture of the government’s pandemic response.

- Include off-budget pandemic measures: This can give the legislature, the public, media, and other stakeholders a comprehensive picture of the totality of the government’s pandemic response, including how much it costs and which parts of the economy and society may be overlooked to date.

- Explain assumptions and uncertainty in fiscal outlook: Budget documentation should (1) explain how COVID-19 has affected the 2020-21 fiscal and economic outlook; (2) clearly set out assumptions underpinning the current outlook—such as breadth and length of economic restrictions, assumed employment recovery characteristics, and assumed impact of pandemic response measures; and (3) appropriately communicate uncertainty and risks in the forecast, possibly through sensitivity or scenario analysis (discussed in more detail below).

- Present the benefits and impacts for different groups in the economy: Analysis showing how different groups, such as the vulnerable, small businesses, or the manufacturing sector, are impacted may help present a more comprehensive picture regarding government support. It will also help the legislature in scrutinizing whether the overall package is appropriately balanced across the different parts of society.

Adopt scenario analysis and contingency planning

In normal circumstances, the government’s budget sets one overarching economic and fiscal outlook. It may add a fiscal reserve to provide cushion against risks to its projections but otherwise the economic and fiscal outlook stands on its own. Given the current level of uncertainty, the IMF and other international bodies have proposed that governments might use scenario analysis and contingency planning to account for uncertainty and volatility in their budgeting. This would in effect see the government establish a range of potential economic and fiscal scenarios rather than rely on a single set of projections. This gives the public and the markets a set of scenarios without limiting the government to a single set of projections that could be soon overtaken by events.

Eurozone countries (the 19 jurisdictions that have adopted the euro currency) are currently using upside and downside scenarios around a central baseline. In June 2020, Eurozone staff produced three scenarios – including the baseline and a mild and severe scenario.[9] The baseline scenario assumed that real GDP declines by 8.7 percent in 2020, the mild scenario assumes a 5.9 percent drop, and the severe scenario projected a 12.2 percent contraction of real GDP. This analysis was then reflected in differing projections for a broader set of economic metrics such as inflation, unemployment, and so forth.

Various international organizations and global think-tanks are also experimenting with different forms of scenario analysis planning in the context of the pandemic. Consider the following:

- The IMF’s June 2020 World Economic Update, which sought to set out global economic projections for the next 4 years, offered a binary scenario analysis between a negative pole in the form of a second pandemic outbreak in early 2021 and a positive pole in the form of a faster economic recovery at the tail end of 2020.[10] It then set out different analyses and economic projections based on these two scenarios.

- In May 2020, the Brookings Institution produced analysis on post-pandemic recovery assuming different types of economic recoveries: these ranged from V-shaped recoveries to the less optimistic W- and L-shaped recoveries. The authors then considered the economic and policy implications for each of these different scenarios.[11]

- At the height of the initial outbreak in March, the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, the country’s independent fiscal watchdog, offered four scenarios based on the pandemic’s potential duration and degree of restrictive government measures. It then produced different economic projections according to these different scenarios.[12] These projections reflected conventional indicators such as GDP growth and public spending.

Scenario analysis planning enables the government to use contingency planning for different economic and fiscal scenarios. Consider, for instance, if the Ontario government’s budget set out three economic and fiscal scenarios – (1) a base case, (2) an upside case, and (3) downside case. This would represent a major step forward for fiscal transparency in the realm of government budgeting in a crisis.

It would also permit the government to develop various policies to reflect the different scenarios. It could, for instance, outline policies that would apply across each scenario as well as ones that would only be implemented depending on how the outlook evolved in the context of which scenario materialized. This would not only give the government greater flexibility to respond to new and evolving circumstances, it would also provide for greater public confidence that the government has a proactive plan rather than a series of reactive responses.

Defining and measuring uncertainty

As mentioned earlier, the IMF has encouraged governments to be transparent about the uncertainty embedded in their economic and fiscal outlooks. One way to do that is to draw on different methodologies for measuring uncertainty in the government’s budget analysis and presentation. The Ontario government, for instance, could contextualize the budget’s economic and fiscal outlook by showing the level of uncertainty over time.

The following are examples of different models that are used by academics and financial sector organizations to measure and track uncertainty:

- CBOE Volatility Index: The Chicago Board Operations Exchange Volatility Index, or VIX (also known as the ‘Fear Index”), is a market index that captures the stock market’s volatility expectations over the next 30-day period. The index is based on price inputs of index options from the S&P 500 and works to convey a generalized sense of financial market risk and investor sentiment. As an illustration of COVID-19-induced market uncertainty, the period from January to March 2020 saw a 500% increase in the VIX[13], triggering the highest register of uncertainty on record at 82.69, which surpasses the previous record of 80.74 set in November 2008.[14]

- Economic Policy Uncertainty Index: As mentioned in the previous section, economists Scott R. Baker, Nick Bloom and Steven J. Davis of the Economic Policy Uncertainty project have created a generalized policy uncertainty index by combining the newspaper-based indices with two more components. One is based on temporary federal tax provisions and tracks the number of tax provisions set to expire over the next 10 years. The other is based on the Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s Survey of Professional Forecasters and records the degree of dispersion between various projections by individual forecasters for the Consumer Price Index, federal expenditures, and state and local expenditures. Together, these are a means of measuring uncertainty caused by macroeconomic factors.[15]

- Equity Market Volatility: There is also a newspaper-based alternative to the VIX, called the Equity Market Volatility (EMV) tracker, which uses the same methodology as the general newspaper-based indices (utilizing specific search terms to scan newspapers for content on the stock market) to gauge the impact of news events on stock market volatility. This measure has found a greater degree of uncertainty from the COVID-19 pandemic than that reached by previous major infectious disease outbreaks like Ebola, SARS and H1N1.[16]

- Business Expectations Surveys: These are attempts to quantify the attitudes and expectations of businesses over a given future timeframe. Surveys like the Canadian Federation of Independent Businesses’ Business Barometer, the U.S. Survey of Business Uncertainty and the U.K.’s Decision Maker Panel do this by asking firms to provide future sales growth projections over a one-year period (or shorter timeframes), which are then used to formulate an aggregate measure of subjective uncertainty. Survey questions may also encompass such factors as projected levels of prices, wages and investment. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 outbreak, the CFIB’s Business Barometer in late March 2020 was at 30.8 index points, slumping by thirty points from 60.5 in February 2020 to the lowest recorded national confidence level in the history of the survey, even including the recessions of 2008 and 1990.[17]

- Consumer Confidence: The Bloomberg Nanos Canadian Confidence Index is a weekly indicator of Canadian consumer confidence compiled through survey data. The survey answers from a random sample of 1,000 consumers across Canada are used to construct a diffusion index with a range of 0 to 100. Scores above 50 indicate net positive sentiment, while scores under 50 indicate net negative sentiment on Canadians views of the economy.[18] The index recorded an all-time low after the coronavirus outbreak in April 2020, falling from the high-50s in March to 42.75%, which ranks as the lowest score recorded since the beginning of this index in 2008.[19]

The Ontario government may want to draw on a combination of these pre-existing indices and the methodologies underlying them to produce its own estimates for the province as part of the budget document. This would help to contextualize its budget planning and give Ontarians a better sense of the level of uncertainty embedded in the budget’s economic and fiscal outlook.

Adopt automatic stabilizers as part of scenario analysis and contingency planning

As a means of accounting for uncertainty in fiscal policy, so-called “crisis budgets” can utilize automatic stabilizers, which are defined as pre-arranged policies and programmes that are designed to “kick in” when the economy hits a pre-set threshold, such as a drop in economy activity or a certain unemployment rate.[20]

There are already automatic stabilizers built into the current fiscal framework: these come in the form of a progressive tax system that delivers revenue increases in times of economic growth, or in the form of increased outlays to income supports like Ontario Works in times of economic contraction. But there is also room for a more conscious approach to the design and deployment of automatic stabilizers – one that can help to bridge the gap between, on the one hand, policy planning and official projections that a crisis budget may lay out and, on the other hand, the unpredictable economic environment. This is particularly true if utilized in conjunction with scenarios analysis and contingency planning.

According to a 2019 essay series published by the Brookings Institution,[21] automatic stabilizers have the following advantages:

- From an administrative standpoint, automatic stabilizers are easier to implement than new, discretionary spending since they are based on budgetary arrangements laid out in advance: there is less need for improvisation and more space and time to focus on efficient delivery;

- For the same reasons, laying out plans in the event of emergency scenarios ahead of time can have a positive effect on household and firm confidence: a programme of automatic stabilizers would help to bolster business and household confidence and allow economic actors to retain a measure of stability and predictability in their spending and investment decisions;

- Automatic stabilizers can ensure that the policy responses contained within the crisis budget are “timely, targeted, and temporary,” insulating contingency provisions from the threat of either premature retrenchment/return to austerity or of going the other way and indulging in more spending than would be necessary;

- In the same vein, because automatic stabilizers entail agreement in advance among policymakers on the scope and scale of relief, it creates a consensus-building effect and a “shared sense of responsibility,” further protecting against political disagreements getting in the way of an effective and on-point policy response.

Making greater use of automatic stabilizers can thus speed up the pace of spending, improve administration and execution, and ultimately mitigate uncertainty and sustain public confidence. Ontario’s policymakers would be well-advised to consider “evidence-based automatic triggers”[22] in the province’s forthcoming budget to activate contingency spending, such as due to a drop in the employment rate or a spike in coronavirus cases. It may be a better approach than improvising policy responses on the fly.

Restoring a fiscal anchor

The Ontario government’s fiscal anchor has been rooted in recent years in the goal of eliminating its budgetary deficit by 2023-24. As discussed earlier, that fiscal anchor has been disrupted by the pandemic. While the immediate-term priority remains addressing the public health challenges and stabilizing the economy, the government should not abandon the goal of long-term fiscal sustainability. It requires a new fiscal anchor as part of its November 2020 budget or in its March 2021 one.[23]

It is not uncommon to temporarily suspend fiscal rules in extraordinary circumstances as the Ontario government has done. Various jurisdictions that operate with a set of fiscal rules (in effect, parameters around deficits, debt, and so on) have “escape clauses” that permit them to deal with immediate crises.[24] Many of these jurisdictions have rules around returning to compliance, including procedures for managing the deficits and debt accumulated in response to the crisis and timelines for restoring the rules. Switzerland is a good example of a jurisdiction with codified rules for managing deficits and debt. When its escape clause is activated, deficits arising from extraordinary expenditures accumulate in an amortization account, which needs to be zeroed out over the next six years by running structural surpluses. Panama is an example of clear parameters for restoring the rules. After its escape clause is activated, the government has three years before it must restore the fiscal rules.

The Ontario government currently operates with a mix of legislated and practical fiscal rules including an expectation that, if the province is running a budgetary deficit, the budget must put forward a plan to eliminate it. The pandemic has obviously caused the government to temporarily escape from these rules and its pre-pandemic fiscal trajectory. As part of its budget planning, it would be useful for the government to re-establish (1) a set of reasonable fiscal rules to govern its fiscal policymaking through the pandemic and (2) a fiscal anchor for post-pandemic fiscal policy.

Balancing uncertainty with fiscal rules is an obvious challenge. There is a risk that narrowly-prescribed rules would constrain the government’s ability to adjust and respond to the ongoing and evolving challenges associated with the pandemic. But, of course, on the other hand, rules that are too loose and flexible could come to justify almost any incremental spending. The balance regarding such tensions will undoubtedly evolve over time as the public health and economic conditions improve. There may be limits on how far the government can go in the short term in restoring fiscal rules but it is ultimately essential to bring back a framework for managing the province’s public finances.

The Quebec government’s balanced budget legislation may be a good model for Ontario. As Marc Lévesque, the president of l’Association des économistes Québécois, recently explained, the Quebec model prescribes the conditions under which a government can run budgetary deficits and spells out the timeframe for when it ought to restore budgetary balance.[25] It also outlines a mechanism for budget surpluses to be set aside in a stabilization fund to offset revenue volatility and pay down debt. As Lévesque puts it: “While Quebec’s framework has come under some strain as a result of the current crisis, highlighting the need for some adjustments, it nonetheless provides a good example of how a set of fiscal rules can work.”

As for a new fiscal anchor, there has been considerable commentary about the right approach in light of the large-scale accumulation of debt in the past several months and the anticipation of ongoing deficit spending for the foreseeable future. Some have argued for an ongoing focus on the debt-to-GDP ratio as the right fiscal anchor. Others have advanced alternatives such as capping debt-servicing costs.[26]

Ontario policymakers should not overthink these questions. The right solution will involve a combination of fiscal anchors that build step-by-step as the province’s fiscal picture improves. It starts with stabilizing and reducing the deficit and then ought to move towards the province’s debt-to-GDP ratio and should ultimately aim to bring greater rationality and predictability to provincial budgeting more generally.

The 2010 G-20 leaders’ statement may be a useful guide. At the time, G-20 leaders committed at their summit in Toronto to at least halve deficits by 2013 and stabilize or reduce government debt-to-GDP ratios by 2016.[27] The specific parameters are themselves not applicable but the basic idea of thinking of fiscal anchors in stages is a worthwhile idea. The timelines for these targets will need to be conservative in light of the ongoing uncertainty but the exercise of thinking through and presenting such targets will be valuable for market confidence, governmental accountability, and internal discipline.

Summary and Policy Recommendations

As has been outlined, the typical approach to provincial budgeting in normal times is not well-suited to the unprecedented uncertainty and volatility associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. The Ontario government, to be most effective, should adjust its usual set of communications and presentational strategies as well as substantive budgeting practices – including scenario analysis and contingency planning – as part of the forthcoming provincial budget.

The government should consider moving in each of the directions set out in the previous sections, including with respect to budget communications, scenario analysis and contingency planning, measuring uncertainty, adopting automatic stabilizers, and restoring a fiscal anchor.

The one area worth further elaboration here is scenario analysis and contingency planning. The Ontario government’s budget already provides sensitivity analysis of how changes in real GDP can affect the province’s budgetary balance. The next step is to use this same sensitivity analysis to establish different scenarios in the province’s economic and fiscal outlook.

Scenario planning is part of the OECD’s “best practices for budget transparency” in normal circumstances.[28] But it is even more important in light of the unprecedented uncertainty in which the Ontario government will table its imminent budget. A range of scenarios relative to a central baseline would help to increase transparency in a moment of great uncertainty and volatility. It could also protect against downside risk to the government’s fiscal projections between the November 2020 budget and its planned March 2021 budget.

The upshot is that the Ontario government should draw on these best practices from academic research and international experience to better position its forthcoming budget to navigate the ongoing uncertainty facing the province.

Sean Speer is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy.

Drew Fagan is a professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy and a former Ontario deputy minister.

Michael Cuenco is a recent graduate of the Master of Global Affairs program at the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy. He has written on public policy issues in such publications as Policy Options, American Affairs, The Monitor and The American Conservative.

For more information about Ontario 360 and its objectives contact:

Sean Speer

Project Director

sean.speer@utoronto.ca

Drew Fagan

Project Director

drew.fagan@utoronto.ca

on360.ca