Policy Papers

Higher Education for Lifelong Learners: A Roadmap for Ontario Post-Secondary Leaders and Policymakers

Andre Cote and Alexi White discuss how two concurrent crises in Higher Education (outdated business models, coupled with COVID19) creates an opportunity to focus on important new population of learners -- working age Ontarians.

Summary

Ontario higher education institutions face two crises.

The first has been slowly building over time, as domestic enrolment demographics worsen; public investment lags inflation; graduates, employers and governments question higher education’s returns to the job market and economy; and increasing pressure on the longstanding “business model” of universities and colleges is masked by soaring revenue growth from international students.

The second crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, places immediate and acute financial and delivery pressures on institutions, accelerating the need for transformation in the adoption of virtual and digital-enabled learning models and in the new demands of learners and employers driven by massive disruption in the workforce. This paper focuses on the opportunity these two separate yet linked crises create for Ontario’s public post-secondary institutions to focus on a new and important population of learners: working-age Ontarians.

Well documented shifts in the nature of work and employer demand are ushering in a new era of “lifelong learning,” requiring workers to access education, training and skills development opportunities throughout their careers to remain current and get ahead.

An emerging, competitive marketplace for lifelong learning is forming globally and here at home. A scan of new approaches for serving lifelong learners—from the United States to New Zealand to Canada — reveals a range of new business models, programs structures, partnerships and pedagogies. Reflecting the needs and demands of these working-age learners, new learning models typically feature shorter, flexible, virtual, work-integrated and demand-driven education, increasingly tied to micro-credentials.

Through a practical lens, this paper is geared to Ontario higher education leaders and administrators who are considering strategies for expanding access to working-age lifelong learners. It is also aimed at provincial policymakers, the stewards of Ontario’s higher education system, who are already in the midst of substantial reforms to both the post-secondary and workforce development systems. For both the province and its public colleges and universities, accelerating the transition to lifelong learning offers compelling value propositions, including new markets of learners to sustain finances, new ways to equip Ontario’s workers for ongoing career success, and new components for the economic recovery plan.

Introduction

Higher education leaders and policymakers are confronted by crisis, but an emerging market for lifelong learning offers new opportunities.

Long before the pandemic, the changing world of work was reshaping the debate around education and skills development. The growing premium on talent in a knowledge-based economy bifurcated the workforce, rewarding the highly-skilled, while a growing number of lower- and middle-skilled Canadians fell behind.

The acceleration of advances in technology and automation risk further amplifying job displacement, skills obsolescence and vulnerability for workers with lower levels of education and skills.[1] In this type of economy, job-relevant education, training and skills development becomes an imperative not only for students preparing to enter the workforce, but for workers who hope to stay employed and advance their careers.

This has placed new demands on higher education institutions. Learners increasingly prioritize their job and career outcomes. Employers call ever more loudly for public sector action to address talent and skills gaps. Governments, in Ontario, Canada and internationally, demand more labour market responsiveness from higher education systems, and use their policy and funding levers to advance these agendas.

Canadian post-secondary institutions, strong in many respects but generally slow in responding to this shifting marketplace, face heightened pressures to adapt missions and business models.

Enter the COVID-19 Pandemic

The pandemic’s impacts on the workforce were immediate and profound. Canada’s unemployment rate more than doubled to 14 percent between February and April 2020, and labour force participation fell by five percentage points as Canadians left the job market entirely. As of October 2020, employment in Ontario remained 3.8 percentage points below pre-pandemic levels, with nearly 300,000 fewer Ontarians in work.[2] Importantly, this pain is being felt unequally across society, with negative impacts more pronounced — and recovery much slower — among less educated workers, women, visible minorities, and Indigenous people.[3] The doubling of the number of people unemployed for over six months is especially worrying, as long-term joblessness results in less successful transitions back to employment.[4]

The impacts on the delivery of higher education have also been significant. Campuses have largely closed; faculty have shifted to online instruction as best they can; and institutions have grappled with a vast array of operational and financial repercussions.[5] Early in the pandemic, there were fears that both domestic and, in particular, international enrolments could collapse with the shift to virtual learning and closed borders.[6] While there remains no reliable data, early indications are that enrolments have overall held up better than expected. The impacts appear highly variable though, with universities faring better than colleges, and larger, more prestigious institutions in better shape than smaller institutions.[7]

Regardless, students report major disruptions to their studies, finances and employment prospects.[8]

The Dawning Era of Lifelong Learning

As the country shifts from pandemic response to economic recovery, higher education institutions, employers in need of skilled workers, and millions of impacted or displaced working Ontarians, may find what each need in the others. The potential addition of new education and training options for a massive emerging cohort of working-age adults who will need to learn, upskill and retrain throughout their careers will serve to reinforce trends that were already driving a new lifelong learning paradigm.[9]

In the new economy, higher education and training systems will have to serve multiple groups of learners, each with different needs. Post-secondary enrolments will likely continue to be concentrated among the traditional core of young, pre-career adults — domestic and international — but working-age adult learners will play an increasing role.

Looking to enhance skills or transition careers, these learners are seeking out lifelong learning opportunities through more flexible, part-time, online and industry-tied models. Labour market disruptions caused by the ongoing pandemic will accelerate this trend.

While this is an enormous opportunity for institutions of higher education, change is difficult in a culture grounded in the traditional full-time, on-campus, diploma- or degree-program models. It will demand a willingness to shift toward modular and micro-credential programs, more employer and industry alignment, more online or blended learning approaches, and flexible competency-based models. This shift, in turn, is likely to reveal new and better approaches to the traditional diploma- or degree-program model as well, just as the pandemic-induced shift to largescale online learning may show that more students are better-served online than previously thought.[10] Government too has an important role to play through a supportive policy and funding environment.

Paper Outline

This paper will focus on the emerging opportunity for Ontario post-secondary institutions to serve working-age lifelong learners in a pandemic and post-COVID world. It will explore emerging models for bold expansion into this market and trace the broad implications for education and training policy in Ontario.

- The first section assesses the shifting landscape for higher education in Ontario, highlighting systems trends and implications for public institutions.

- The second section describes the emerging marketplace for lifelong learning, focusing on the profile of working age learners, the new types of players and systems that are emerging to serve them, and the opportunity in Ontario.

- The third section presents a scan of new educational models for serving working-age lifelong learners, profiling compelling provincial, national and international cases, with key takeaways for higher education in Ontario.

- The fourth section considers practical strategies and considerations around catalyzing this transition to lifelong learning models in Ontario, geared to both leaders of post-secondary institutions and to provincial policymakers.

1. The Shifting Landscape for Higher Education and Skills Development in Ontario

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented challenge for Ontario’s higher education system.

For the province’s 45 public colleges and universities, the sudden shuttering of campuses and the large-scale shift to virtual learning formats has been an extraordinary shift in how higher education is delivered. Fears over enrolment collapse for the fall 2020 semester didn’t bear out, but there has still been a deterioration in university and college finances.

In recent years, almost all new revenue in the sector could be traced back to growth in international student enrolment, leaving many institutions financially vulnerable. Many hope that campus life will return to normal when the pandemic recedes. But will it?

Ontario’s higher education system has traditionally performed well. It boasts a few globally recognized research-intensive universities, a number of mid-sized polytechnics, colleges and universities with strong and differentiated programmatic mixes, and a series of smaller institutions that serve as important educational anchors to their local communities.

The province’s population has among the highest share of post-secondary credentials in the OECD, with graduates continuing to make strong societal contributions while benefiting from the financial returns of their education.[11],[12] Yet, even prior to the pandemic, there were stresses at both systemic and institutional levels.

First, traditional teaching and learning models have not adapted adequately to changing student demands and labour market needs. Higher education — particularly the university sector — has been confronted with a growing list of critiques to the still-dominant, campus-focused program models: long and relatively inflexible programs; inadequate recognition of prior learning; slow or limited innovation in pedagogy; insufficient student supports for career-readiness; weak alignment to labour market needs; and a limited commitment to online and digital-enabled learning.[13],[14]

In particular, students and parents are increasingly demanding that higher education programs lead to clear employment outcomes, with employers expecting a higher level of job readiness among graduates.[15],[16] This has led to some promising developments, such as investment and mobilization around work-integrated learning (WIL). Yet, commitments like expansion of WIL, which bolts onto the traditional academic model, allow the sector to signal change without fundamental programmatic and pedagogical innovation. This partly results from cultural resistance in the academy. Emphasis on skills development and employment outcomes has been critiqued as an attack on the mission of higher education to engage personal interests and intellectual discovery. This presents a false choice; new approaches can produce better results across all these dimensions without sacrificing the tried and true foundations of higher education.

Second, some public institutions face threats to their financial sustainability, which COVID could be amplifying. Over the past decade, the provincial government’s per-student funding of Ontario’s post-secondary institutions has fallen by one percent in real terms, and remains the lowest in the country.[17] Demographics are shrinking the population of 18-to-20 year in Ontario, posing a risk to domestic enrolments.[18] Institutions’ expenses have nevertheless continued to grow rapidly, and are largely fixed under current administration and faculty models. Labour costs represent, on average, 63 percent of a college budget and 75 percent of a university budget.[19]

The gap has been filled by a tripling of international student enrolment over the past decade; the system has rapidly become addicted to international money, most significantly in Ontario colleges.[20],[21]

Already vulnerable institutions have limited options in this crisis, especially if international enrolments remain depressed post-COVID. Increased revenues via domestic student enrolment is not a viable alternative unless governments fund additional seats or relax tuition regulations. Large provincial deficits suggest institutional grants will not increase and could in fact fall in the coming years.

In short, pre-COVID financial stresses could be amplified, particularly for rural and northern institutions.

Laurentian University, for example, already facing a $9 million budget gap for 2020-21, saw its fiscal shortfall balloon with COVID.[22] A 2017 analysis of the fiscal condition of Ontario’s colleges projected that, over the period to 2024-25, existing structural shortfalls could result in a cumulative operating deficit across all 24 colleges of over $400 million annually.[23]

The provincial post-secondary policy agenda continues the shift toward differentiated mandates, performance-based funding, and alignment with economic and workforce priorities. The Government of Ontario is negotiating a third round of Strategic Mandate Agreements (SMAs) with the 45 colleges and universities, and trendlines point to more assertive government mandates and related conditions for post-secondary institutions. The SMAs are linked to a more performance-based model linked to 10 metrics including post-graduation employment rates, WIL opportunities and other skills and economic indicators. The Progressive Conservative government signalled a dramatic escalation in performance-tied funding, to 60 percent of operating grant funding, though this shift has been paused as a result of the COVID-19 crisis.[24]

The provincial government has also backed an initiative led by eCampusOntario, recently expanded in the 2020 Ontario Budget, to incubate industry-linked micro-credential programs in the post-secondary system, with the aims of speeding skills training, supporting lifelong learning and improving responsiveness to labour market demand.[25],[26] This aligns with the federal government’s talent and skills agenda, including the new Canada Training Benefit that offers financial assistance to working-age learners, and the Future Skills Centre mandate to spur new education and training models for a changing labour market.[27] The provincial transformation of the Employment Ontario system to a performance-funding model, delivered through a network of private and nongovernmental Service System Managers (SSM) across 15 regions, will also have implications for higher education. The selection of Fleming College as pilot SSM for the Muskoka-Kawarthas region will be explored in more detail later in the paper.

Taken together, the ongoing challenges to higher education, the emerging policy agenda at Queen’s Park, and the effects of the pandemic, create many of the preconditions for a shift toward lifelong learning models.

2. The Emerging Marketplace for Lifelong Learning

The world of work has been changing rapidly. In Canada and other western countries, headline indicators like low unemployment have masked deeper, structural workforce trends and challenges. Research has documented factors such as the shift from stable, full-time employment toward precarious freelance, part-time or “gig” economy work;[28] the workforce disruption and skills demands amplified by advances in technology and automation;[29] and the labour market barriers faced by groups such as older displaced workers, social assistance recipients, and racialized BIPOC communities.[30] A recent report from the Public Policy Forum identifies five key changes affecting workers:

- A decline in routine work;

- An unbundling of tasks;

- A greater need for adaptability and resilience on the part of workers;

- A premium on workers’ ability to work with technology; and

- An increased emphasis on hard-to-automate skills.[31]

Employers consistently report challenges finding talent and closing skills gaps. Yet, industry in Canada has faced criticism for years for its lack of human capital investment.[32],[33] When employers do invest in training their staff, it tends to be for already highly-skilled workers. They benefit from about 70 percent of average training budgets and receive more intensive training than lower-qualified employees.[34] Those less likely to receive workplace training include low-skilled, Indigenous and older workers, and the effects are exacerbated if living in rural or remote communities.[35]

At the same time, where employers look to the higher education system for new talent, they report that graduates are often not “job-ready.” A HEQCO study of graduate skills, applying a pilot approach with 20 Ontario colleges and universities, found that one in four graduating students was below adequate in measures of literacy and numeracy, and less than a third were at superior levels.[36] Other research finds that nearly half of Canada’s workforce has lower skills than required to fully participate in the labour market.[37] While higher education voices dispute these findings, skills gaps surely contribute to the market disconnect that the Ontario Chamber of Commerce and others have described as: “not enough jobs for people, not enough people for jobs.”[38]

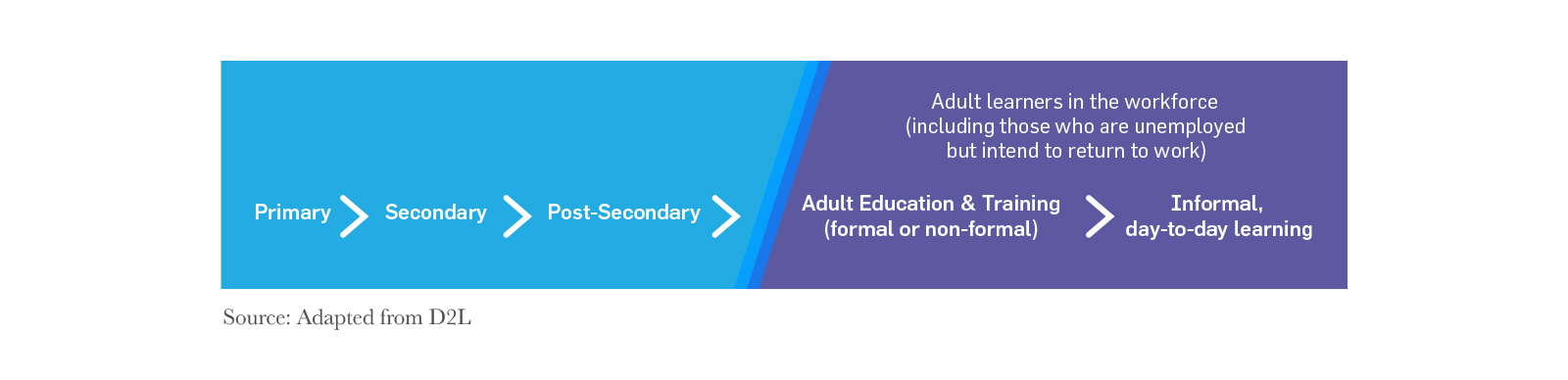

In Canada and abroad, rapidly changing labour markets and skills demands are leading to calls for a major expansion of lifelong learning. A recent “white paper” by Canadian education technology company D2L took a broad lens in surveying the current landscape for lifelong learning.[39] It zeroed in on adult learners in the workforce as the target segment, requiring ongoing education and upskilling throughout their working life. Building on OECD definitions and typologies, lifelong learning was described in three forms: formal education and training toward a credential; structured, semi-formal education and training that may or may not lead to a credential; and informal learning through work and life.

Figure 1: The Lifelong Learning Continuum

The demand among working-age learners, despite limited evidence, is presumed to be large. Globally, a large survey of employers conducted by the World Economic Forum found that, by 2022, the average worker will require 25 days per year of training and skills development — or nearly half a day per week.[40] An admittedly rough proxy for demand, it gives a sense of the potential scale of the marketplace for lifelong learning in Ontario, with a provincial labour force of approximately 8 million people. When asked in a 2017 survey, over 30 percent of working-age Canadians expressed a desire to complete additional training, but felt that barriers in cost and time prevented them from doing so.[41] Experience south of the border provides further evidence, as institutions catering to a working-age demographic have seen significant growth in enrolment.[42]

Among working-age learners and employers, there is further evidence of demand for new forms of short-duration micro-credential programs. A 2020 survey conducted for Higher Education Strategy Associates (HESA) estimated a potential market of over seven million Canadians (proportionately, about three million Ontarians) for new micro-credential programs, provided they are offered with sufficient flexibility, brevity and specificity in skill development.[43] While awareness of micro-credentials is still limited, 80 percent of employers and employees surveyed expressed interest in micro-credential programs once they fully understood the concept. In the more mature U.S. market, 68 percent of adults considering enrolment in education prefer non-degree pathways, up from 50 percent a year ago.[44] The HESA survey found that “having a prior track record of issuing quality credentials is important for credibility and acceptance,” suggesting that public institutions may have an advantage over new entrants to the market.

Micro-Credentials

The concept of short courses and programs is not new, but it is enjoying a resurgence. The term micro-credentials refers to a category of short-duration credentials predominantly designed in partnership with industry that may or may not confer academic credit applicable toward longer programs. Certificates composed of massive open online courses (MOOCs) can be considered a type of micro-credential, as can digital badges meant to signify mastery of a defined skill or knowledge set and may rely more heavily on prior learning recognition. As recent additions to the higher education landscape, the use and definition of these terms varies across jurisdictions, and the labels mask huge variation in duration, pacing, cost, delivery, assessment, portability and authentication.

In Ontario, efforts are underway to establish common definitions, characteristics and standards of micro-credentials. A number of institutions and employers have worked with eCampusOntario in the development of the Micro-credential Principles and Framework, with the Council of Academic Vice Presidents (OCAV) and HEQCO also reportedly exploring the issue.[45]

Early research into the return on investment for short-duration credentials is promising. A recent Statistics Canada study tracked over 5,000 people who earned an undergraduate degree in 2010 and went on to complete an additional short-duration credential at a college or university in the next six years. Many of these graduates had lower-than-average employment income prior to enrolment, but saw income rises that nearly closed the gap with non-school returners after completing a short-duration credential. The proportion of graduates employed in “low value-added service industries” fell by more than half.[46] The emergence of income share agreements (ISAs) further tightens the link to post-graduation employment outcomes. The use of ISAs, which substitute up-front tuitions for a percentage of learner income once employed, is growing south of the border, and Toronto’s Juno College recently became the first private career college in Canada approved to use ISAs.[47]

In response to this demand, the higher education and workforce development field is becoming more crowded and competitive. In the United States, non-profit institutions such as Western Governors University and Southern New Hampshire University have pursued this new market and are now serving hundreds of thousands of working-age learners through affordable, online, open-enrolment and skills-focused programs. An array of private players is angling to capture this market too, ranging from private online universities (for instance, University of Phoenix) and fee-based MOOC providers (Coursera), to à la carte online course repositories (LinkedIn Learning), private career colleges (General Assembly and other coding schools) and education and workforce training companies (Maximus). In June, Microsoft announced an ambitious program with GitHub and LinkedIn that aims to bring digital skills to 25 million people worldwide by the end of this year.[48]

Many of these players are now active in the Ontario marketplace, as competitors or collaborators with public institutions. In addition to the large online providers, GUS International and Northeastern University have opened campuses in Toronto.[49],[50] A large community of private career colleges (PCCs), including a new breed of Canadian coding schools like Lighthouse Labs, compete with public institutions for learners. Many PCCs are eligible for provincial student aid or public training dollars. Large multinational entrants WCG Services and FedCap, competitively selected alongside Fleming College as pilot SSMs in the reformed Employment Ontario system, may have significant influence in steering the province’s workforce development system.[51]

The Profile of Lifelong Learners

Ontario has a large, diverse population in an equally broad economy that requires a wide variety of skills and learning needs. Research by HEQCO presents a skills spectrum for lifelong learning.[52] On one end are low-skill learners, requiring literacy and basic skills training, employment services and social programs. Higher education is generally not equipped to support these individuals, who are more likely to access the employment, training and workforce development programs offered through Employment Ontario. At the other end of the continuum are highly skilled learners seeking elite, high-cost professional programs like executive MBAs or leadership development training. There is already a well-established, competitive market for them, often paid by employers.

Between these poles is a diversity of middle-skilled workers across industries and occupations, each with unique challenges and goals. Some are in need of a short course to keep skills current or secure a promotion; others are looking to make a career change and require more intensive education towards a new credential— preferably one that provides credit for what they already know.[53] The typical motivations of these learners include:

- Career benefit, as well as earnings related factors (to keep a job or advance to a new one; to secure increases in pay and benefits).

- Seeking non-degree credentials and skills-based education and training, through flexible, online and asynchronous models to fit into a busy life.

- Low cost options, particularly where they do not have access to training and development programming or financial support through their employer.

- Common challenges with participation and completion include time commitment, logistical factors like time away from work or course schedules, and self-doubt about their ability to return to school.[54]

Picture, for instance, a 45-year-old Walmart cashier, with a high school education, who recognizes the need to upskill to have a shot at a job that offers better pay and advancement; or a 30-year-old restaurant server, out of work during the pandemic, who wants to build upon their undergraduate degree to pivot into a new career.

Successfully serving these busy working adults requires changes in the traditional form of higher education, such as new approaches to marketing and recruitment, more flexible or rolling admissions, more explicit learning pathways and career outcomes, more standardized and skills-focused curriculum, and wrap-around student supports that reflect the different kinds of day-to-day challenges that these learners face.

Post-secondary institutions have not yet embraced new models of program design and delivery that have been successful elsewhere. While young adult learners place more value on a campus experience with strong social elements, working-age learners can have very different needs. This requires a shift from the prevailing full-time, on-campus, degree-program models toward more short, modular and micro-credentialed programs; more employer and industry alignment; more online or blended, as well as competency-based models that are still relatively unknown in Ontario;[55] and better services and social supports for online learners.

The 2019 National Survey of Online and Digital Learning suggests Canadian post-secondary institutions understand the importance of shifting to new technologies, delivery methods, and types of credentialing; however, a minority of institutions are at the stage of implementing their plans: “The results continue to illustrate a paradox between the stated perception that online education is important for institutions compared to the implementation status of strategies for online learning.”[56]

Finally, governments are making ambitious moves toward lifelong learning. While the Governments of Canada and Ontario have introduced promising new initiatives, other countries are taking bolder steps. U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson recently announced a “lifetime skills guarantee,” with every low-skilled adult offered a lifelong entitlement to four years of free further education from a list of approved programs tied to labour market demand.[57] He described the aim of the plan as eliminating “the senseless barrier between further education (skills training) and higher education.”[58] To support economic recovery, the New Zealand government introduced free vocational training in critical industries for all Kiwis for two years. Qualifying courses are linked to industry needs in sectors such as building and construction, agriculture, manufacturing, community health, counselling and care work.[59] In Australia, the government is offering low-cost, six-month online courses tied to high-demand occupations to support displaced workers with career change.[60]

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis is a further catalyst. The unprecedented social and economic disruption is driving demand among working-age learners for online delivery of up-skilling and retraining programs. For example, the popular MOOC platform Coursera saw enrolment skyrocket to 640 percent year-over-year in March and April of this year, with competitor Udemy’s enrolment up over 400 percent.[61] Online course providers, coding bootcamps and business schools in the US have reported a surge in interest in non-degree online credential programs from current students, recent graduates, and furloughed or laid-off workers looking to change careers.[62] Some post-secondary institutions may see this as an opportunity that can be capitalized on; others may face pressure from governments to respond to

this need.

3. New Models for Serving Lifelong Learners

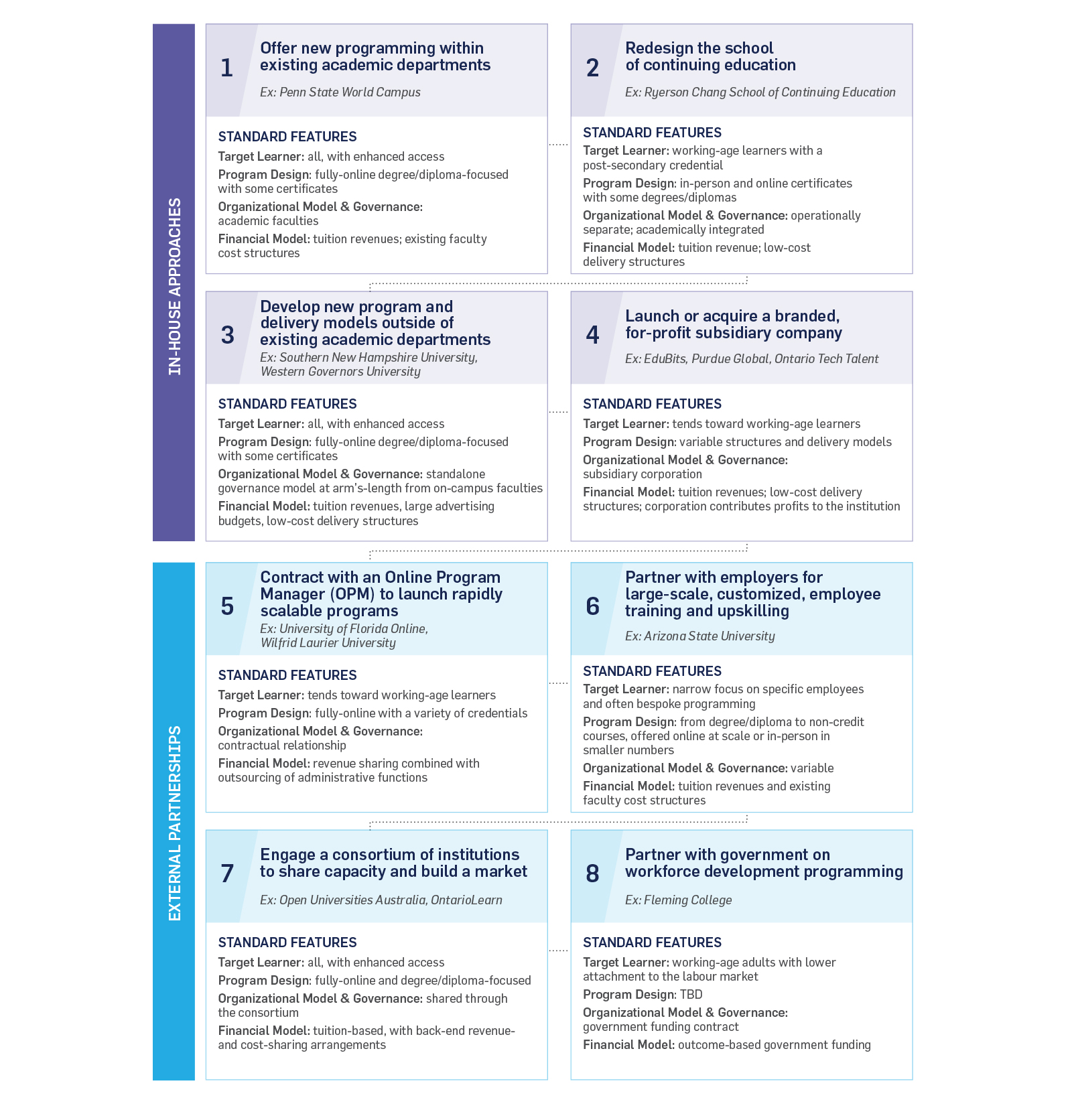

In this section we survey how public and non-profit higher education institutions in Ontario and internationally are expanding their offerings for working-age lifelong learners. We group the analysis into eight emerging models that are roughly divided into two categories:

- in-house approaches developed under the full control of the institution, and

- external partnerships where the institution leverages its shared interests with the private sector, government or other institutions.

Though neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive, these categories and models illustrate the wide range of approaches being employed. The summary table below captures their standard features: target learner, program design, organization model, and financial model.

Figure 2: Summary Table—Emerging Models for Serving Lifelong Learners

In-House Approaches

1. Offer new programming within existing academic departments

Perhaps the most obvious pathway to expanding offerings for non-traditional students is to build new capacity in-house through existing academic departments.

A prime example is Penn State World Campus, which was launched in 1998 to offer online education to learners who could not access an in-person education for a variety of financial, geographic or other circumstances. World Campus offers over 150 online degree and certificate programs taught by the same faculty who teach on campus, all integrated with Penn State’s academic and student-support infrastructure. Strong recruitment and marketing have been key to Penn State’s success, as has a long history and cultural acceptance of distance learning, which dates back as far as 1892.[63] Penn State has largely eschewed the hyper-growth approach to online learning followed by some of its competitors, but with 14,500 fully online students in 2018 it ranks in the top five in online enrolment among public institutions in the U.S.[64]

Other U.S. public universities have seen less success, or outright failure. One infamous example is the University of Illinois Global Campus, which launched in 2008 with a mission to expand access to higher education to non-traditional and place-bound students. The project was wound down the following year, however, as a result of disappointing enrolment numbers and faculty resistance.[65] The University of Texas (UT) took a different approach to improving access for non-traditional learners, creating the Systems Institute for Transformational Learning as a kind of internal tech startup to develop the learning platforms, online courses and other technology needs for the UT system.[66] After spending $75 million over six years, the Institute was cancelled in 2018, with observers blaming a poor business plan and, again, faculty resistance.[67]

2. Redesign the school of continuing education

Schools or departments of continuing education are common at Ontario colleges and universities. Separated from the institution’s core academic departments, they typically offer a range of credit-bearing and non-credit-bearing courses and certificates accessible both online and in-person.

A typical learner may be interested in exploring a new hobby, developing a new skill, or pursuing a new career path. Where an institution as a whole may be slow to capitalize on growing demand for lifelong learning, continuing education units are often much more agile.

Ryerson University’s G. Raymond Chang School of Continuing Education is perhaps Ontario’s most successful example, boasting 84 certificate programs, over 1,300 courses, and over 70,000 enrolments annually. One of the Chang School’s defining characteristics is its culture of integration with Ryerson’s academic departments. Most continuing education certificates are Senate-approved for academic credit, and the same course may be taught simultaneously in an academic department and at the Chang School. This connection makes much of Ryerson’s continuing education stackable, meaning a series of shorter offerings can be combined to form a higher-level credential. For example, students can move seamlessly from a certificate into a part-time degree. It also allows Ryerson students to easily access Chang School offerings, and many graduate with both a degree and a certificate.

Like most continuing education in Ontario, Chang School courses are primarily taught by contract lecturers who often have industry experience in addition to academic qualifications. A “collaborative model” is used to spell out the partnership between the Chang School and Ryerson’s faculties, and academic coordinators are appointed in consultation with the faculties to ensure the quality of continuing education meets the faculty’s own standards.[68] Ryerson University’s history as a career institute, polytechnic, and then university, has created a strong cultural foundation for this model. At other institutions, continuing education is sometimes hived off from the rest of the enterprise and largely forgotten or divorced from the broader conversation about innovation in digital pedagogy and program design.

The Chang School offered 35 online certificate programs prior to the pandemic and has quickly shifted most of its offerings online since. Forecasts of higher pandemic-induced demand for online adult learning appear to be accurate, with the school’s enrolment up over 50 percent for the Fall 2020 term.[69] Interestingly, the Chang School also doubles as the online learning development unit for Ryerson as a whole.

Four-in-five Chang School students already have a post-secondary credential. Chang School Dean Gary Hepburn sees growing demand and new opportunities, particularly through industry-specific offerings. For example, the school hopes to make a large splash in the micro-credential market in the coming years, including through partnerships with employers and nonprofits to offer focused, bespoke training. Quality and stability will remain a core tenet so that learners can move from micro-credentials to certificates to degree programs.[70]

3. Develop new program and delivery models outside of existing academic departments

Some of North America’s largest providers of lifelong learning for working-age adults credit their success to more flexible, innovative approaches that are often easier to realize outside of traditional academic structures.

While private, for-profit colleges such as the University of Phoenix were the first to demonstrate the mass market potential for online degrees marketed to working adults, non-profit providers Western Governors University (WGU) and Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU) have emerged as among the most successful online mega-universities in the United States.

In the mid-1990s, the governors of several U.S. states pooled resources to found WGU as a standalone online-only institution. SNHU also launched its first online programs in the mid-1990s, and similarly opted to separate this part of its operations from its campus-based academic programs that date back to 1932. In both cases, this separation has allowed the institutions to cater to the needs of working-age online learners and to sidestep criticism that a corporate approach and transactional learning experience undermines traditional university values of discovery and independence.

Both institutions can trace their success to the similar innovations and willingness to stray from traditional university norms in an effort to attract and support adult learners.[71] They embraced a flexible competency-based education model where prior learning is recognized and students advance by demonstrating proficiency in the remaining competencies, rather than completing course hours and course work on a specific schedule. They have also developed rapid admissions processes that minimize the administrative burden on students, and they invest tens of millions each year — about a fifth of total revenue — in aggressive marketing strategies focused on the target market of 30 million Americans who have some college credit but never graduated.[72]

Unlike the University of Phoenix, greater emphasis on early intervention and student support has seen both WGU and SNHU reach graduation rates that, though still low, are nearing national averages, even as their student demographics skew toward underserved groups. Whether it is their success that has driven a culture change, or vice-versa, both institutions seem to have moved past the affinity for scarcity and prestige that continue to have a profound influence on university culture.

Western Governors University

With well over 100,000 students in 2019, and enrolment continuing to grow at pace, WGU is among the largest online universities in the United States.[73] Although over 90 percent of students are adult learners, the 18 to 22 year-old age group is growing at five times the rate of WGU enrolment as a whole.[74]

One of its defining characteristics is its use of competency-based education, where credits are awarded by demonstrating competency and where time to completion is up to the individual student. WGU has also developed an unusual model of instructor specialization that splits the design, teaching, and evaluation roles that would traditionally be the responsibility of the same instructor. With so much of the learning experience “unbundled”, each student is assigned a program mentor to help maintain a stable connection with faculty and to help the student create and stick to a personalized learning plan.[75] WGU’s leadership predicts continued growth in demand for degrees among adult learners,

and increased unbundling of degrees with the rise of stackable micro-credentials.[76]

4. Launch or acquire a branded, for-profit subsidiary company

As a variation on the previous model, some institutions opt to separate their lifelong learning operations by launching a new brand as a for-profit subsidiary. This tactic is more often used when the institution wishes to provide an innovative approach that goes beyond the usual higher education offerings; for example, when expanding into micro-credentials and the upskilling or reskilling arena.

In New Zealand, Otago Polytechnic launched a spin-off company in 2017 called EduBits that styles itself as the first micro-credentialing service in New Zealand. EduBits now offers over 100 stackable micro-credentials, each of which is referred to as one EduBit.[77] Individuals can enrol directly, or businesses can partner with EduBits to develop customized offerings or to have their existing offerings credentialed through EduBits. With start-up costs of around $1.5 million NZD, the company hopes to break even in 2020 and begin generating a profit in future years.[78]

EduBits uses a number of innovative tactics to keep development costs low. Content designers are all external to Otago Polytechnic, but the company retains a modified, informal version of the institution’s academic approval process. A just-in-time development process is sometimes employed, whereby content creation is triggered only if sufficient interest has been identified six weeks ahead of the proposed launch of a new EduBit.

According to Otago President Phil Ker, EduBits was designed as a response to the waning value proposition of more traditional education models. Nationally, New Zealand’s ambitious plan to unify its 11 apprenticeship training organizations and 16 institutes of technology and polytechnics under one vocational education system may create the right conditions for rapid spread of innovations such as EduBits.[79]

U.S.-based Purdue University took a different approach in establishing a branded subsidiary, acquiring for-profit Kaplan University for $1 in 2018. Rebranded Purdue Global, it acts as a kind of in-house online program manager (OPMs are described at length below).[80] Although Purdue paid little up-front, it agreed to a lengthy contract to buy support services from parts of the Kaplan operation that will remain tied to a for-profit business. Kaplan will provide all non-academic support services such as recruitment, admissions, human resources, marketing and technology support for 30 years, and Kaplan receives 12.5 percent of revenue, as long as funds are available after all operating expenses and guaranteed payments to Purdue have been covered. This model may be catching on, as the University of Arizona recently announced it will acquire the online Ashford University and its roughly 35,000 students, rebranding it as University of Arizona Global Campus.[81] Consolidation of online learning providers is expected to continue, and may lead to more of these deals in the future.

Closer to home, Ontario Tech University announced in February 2020 that it is launching Ontario Tech Talent as a for-profit subsidiary of the university.[82] The new entity will serve as the operational vehicle to deliver a new initiative focusing on employment readiness and upskilling for students and new graduates. While the initiative is nascent, it envisions a system of credentials and micro-certifications to better serve industry, workers and graduates. It will allow industry partners to license modules and deliver training themselves, take advantage of online programs, or send employees to train at the Ontario Tech campus. To launch the new entity, Ontario Tech Talent received a $500,000 loan from the university for operating expenses in its first few years, and projects to become self-sustaining in its third year (2022-23), at which point it hopes to return profit back to the university.

Purdue Global

Purdue Global, formerly Kaplan University, offers online education tailored specifically to working adults interested in pursuing a degree of any level, from associate to PhD. It offers over 175 programs, with content delivered mostly online, though there are a limited number of classroom locations. A number of competency-based, flat-fee options are offered under the brand ExcelTrack. Purdue University, which did not have a significant portfolio of online degree offerings prior to acquiring and rebranding Kaplan, immediately became one of the largest online providers in the country. Purdue Global is structured as a public-benefit corporation, allowing it to pursue goals in addition to maximizing profit for shareholders. Initial growth has been slower than hoped, and Purdue Global has not yet turned a profit. Loses in 2019 were around $16 million, down from $38 million the year

before. The company is hopeful that it can break into the black in 2020.[83] Purdue’s approach was not without controversy in the university community. The administration argued that the partnership would advance its mission as a land-grant university by providing access to higher education for tens of millions of working adults. Opponents countered that money is the true motive, and that Purdue is enabling a slow privatization of higher education.[84]

External Partnerships

5. Contract with an Online Program Manager (OPM) to launch rapidly scalable programs

Another model for expansion into online offerings is to contract with an online program manager (OPM)—a private, for-profit developer such as Wiley, Pearson, 2U, or Academic Partnerships. Institutions of all kinds have engaged in these partnerships, from UC Berkeley’s successful masters in information and data science program in partnership with 2U, to the partnership between iDesign and the small for-profit Schreiner University for an online nursing program.[85] Now a common model in the United States, the number of OPMs has tripled in the past decade. Comparative data is scarce, but Academic Partnerships appears to be the largest OPM in the U.S., boasting over 60 institutional partners and managing over 650 online programs as of 2018.[86] OPMs have recently begun to enter the Canadian higher education market. In 2020, the North American OPM market is projected to be worth over $2.7 billion.[87]

OPMs are a natural option for institutions that are looking to quickly develop an online offering — say a short-duration certificate program — but lack the development capacity to get the courses up and running online, the funds to advertise it, or the administrative capacity to handle enrolment and other related transactions. Often, the institution is confident there is sufficient learner demand to make the program successful, but without external support the program could never be launched.

In a typical OPM contract, the institution hands over responsibility for some elements of course development and operations to the OPM, along with a portion of total tuition revenues. The contracted services may vary considerably based on the institution’s needs. In some cases, the OPM will assume nearly all development and operations, and may be rewarded with half or more of total tuition revenues. Because the OPM is often bearing most of the financial risk, they may be selective in the programs they agree to develop in order to ensure a strong future revenue stream.

OPM partnerships can have a dark side. The worst examples involve lengthy, unbreakable contracts for bundled services, paid for through a shared tuition revenue model that incentivizes aggressive recruiting. As noted by the Century Foundation, a U.S.-based think tank, “programs where OPMs control the majority of course development and operations in exchange for a share of tuition revenue expose students to the same risks involved with enroling in a for-profit college, but with even less protection than those students receive, since an online program is run under the guise of a public institution.”[88] A high-profile example of OPM failure is the University of Florida Online (UF Online), which terminated its eleven-year contract with a large OPM after failing to meet ambitious growth plans. It has since had more success with a less ambitious growth plan.

In Ontario, Wilfrid Laurier University (WLU) took a more measured approach in a recent OPM partnership. WLU contracted with Keypath Education in 2016 to offer the university’s first two programs to be delivered entirely online.[89] Keypath provides student recruitment and student support services for online offerings, as well as strategic support and program-focused marketing. The programs were designed specifically for those who benefit from the increased flexibility; for example, the BA in policing was open only to current police officers, who would have significant barriers to accessing in-person or non-flexible programs.

WLU had solid evidence of demand for its new degrees, but as WLU’s assistant provost for strategy put it: “It became clear that we didn’t have the internal capacity to do this properly, so we needed a partner to reach this goal.”[90] When enrolment in the first two programs exceeded projections by 70 percent, the university added specialized programs in social work and public safety in 2017, and in computer science in 2018. In each of these cases, WLU has been selective in its choice of programs for online offerings, picking high demand areas that are conducive to online delivery.

University of Florida Online (UF Online)

Backed by $35 million in special financing from the state legislature, the University of Florida opened UF Online in 2013 on a tight timeline and with ambitious plans to enrol 24,000 students annually within 10 years. With a large portion of students paying out-of-state tuition fees, UF Online hoped to generate $76 million in revenue and $14 million in profit annually at maturity. The concept was to offer fully online baccalaureate programs at a lower cost and with the same level of quality as the on-campus alternative.[91] UF tapped Pearson as its OPM to rapidly adapt the university’s existing programs into the online space.

In 2015, with UF Online missing its enrolment targets, the university canceled its eleven-year contract with Pearson. Services previously provided by Pearson, such as admissions, recruitment, marketing, and student support, would either be managed in-house or outsourced to new partners.[92] The future of the UF Online seemed in doubt. As one commentator noted, “UF Online risks becoming the new poster child of online education failures.”[93]

A year later, however, with admissions up 70 percent, UF Online posted a small profit of $66,000. Less ambitious growth plans now anticipated 6,500 students by 2020, almost all of them in-state.[94] In 2018, the University of Florida enroled 4,766 students in fully online programs, far behind the big players in U.S. online education and less than half the enrolment at local competitors Florida International University and the University of Central Florida. Despite these low numbers, UF Online’s commitment to quality seems to have paid off, with its undergraduate program now ranked fourth in the country according to U.S. News and World Report.[95]

6. Partner with employers for large-scale, customized employee training and upskilling

Corporations have long offered programs that incentivize lifelong learning among their employees. In recent years, corporate interest has noticeably increased, leading to a boom in exclusive partnerships between companies and higher education providers. For the academic institution, these partnerships present a captive market with much less need for aggressive marketing and recruitment strategies. For the employer, offering education and training through reputable higher education providers is a retention tool and a long-term investment in the quality of employees.

One of the higher education leaders in this area is Arizona State University (ASU). Its corporate partnerships have driven substantial growth in online enrolment, which has nearly doubled to 37,000 students between 2015 and 2018. ASU now offers over 200 undergraduate and graduate degrees with six start dates per year. Since 2014, ASU and Starbucks have partnered on the Starbucks College Achievement Plan. Under the plan, benefits-eligible Starbucks employees studying in over 80 ASU online undergraduate programs can have their tuition fees covered through a combination of scholarships, government aid, and other reimbursements.[96] As of spring 2019, nearly 3,000 employees had graduated from ASU, and there were about 12,000 Starbucks employees enroled in ASU classes, accounting for 27 percent of all ASU online students that semester.[97]

This kind of direct partnership, novel in 2014, is now more commonplace. ASU has added a similar arrangement with Uber; eligible Walmart employees can now study toward an online degree from the University of Florida, Brandman University, or Bellevue University for $1 a day; and FedEx Express partnered with the University of Memphis Global to design custom degree programs that are free for employees.[98],[99],[100]

In 2019, ASU doubled down on the corporate partnership model, joining with the Rise Fund to create a public-benefit corporation called InStride. The new firm seeks out and partners with corporations to develop “custom employee education programs” delivered through one of InStride’s nine preferred academic institutions around the world, including ASU.[101] InStride describes the problem it is solving for: “Corporate America spends $180 billion each year on tuition assistance and corporate-sponsored training programs…. [yet companies] are dissatisfied with these programs because they don’t produce the desired business results.”[102] InStride is betting that employers will continue to invest in tuition reimbursement programs to upskill and retain employees, and that the future lies in bespoke programs tailored to the company’s needs.

7. Engage a consortium of institutions to share capacity and build a market

Given the right circumstances, higher education institutions sometimes choose to share capacity and risk through the formation of a consortium. With long-term competition for online learning inherently more global, there can be a strong business case for local cooperation under a shared brand.

Open Universities Australia (OUA) offers one successful example. OUA’s mission is to expand access to higher education, particularly for lifelong learning. Serving about 350,000 learners, OUA students can access over 350 degree programs composed of online courses offered through 17 Australian universities, with no academic entry requirements for most undergraduate subjects (i.e. “open” enrolment).[103] Students have some ability to customize their degrees, accessing courses from multiple universities while still graduating with a degree from the institution where they completed the majority of their courses. OUA also offers a range of shorter courses marketed to working-age adults seeking upskilling or reskilling opportunities.[104]

In the 2010s, OUA expanded into new lines of business—vocational education and training, corporate training, online education services, and the free online course platform Open2Study. However, a number of years of overall declining enrolment caused the Board of Directors to refocus solely on its main higher education mission.[105] While OUA’s expansion plans faltered, the consortium model offers institutions the ability to share the risk of entering these markets.

OntarioLearn, another successful consortium approach, has enabled all 24 Ontario colleges to share over 800,000 course enrolments. In the mid-1990s, OntarioLearn began as a collaboration of four publicly-funded colleges which realized they could maximize resources by sharing the provision of online courses rather than duplicating at each institution. OntarioLearn now includes all 24 publicly-funded colleges, offering over 1,500 courses to over 80,000 students, and enjoying 5.6 percent enrolment growth in 2019.

Under the OntarioLearn model, individual colleges host specific courses, for which they are responsible for content, delivery, quality and student evaluation. Other colleges in the consortium are then able to add these courses to their own offerings, allowing their students to access a larger number of courses without the costs of delivering these courses themselves. Students enrol and pay for courses through their home college, with OntarioLearn infrastructure and its small staff funded through college membership fees and a per-enrolment administration fee. While OntarioLearn provides 24/7 technical support for their online courses through a third-party server, all other student services are provided by the student’s host college. As a result, students experience each course as if it is offered through their home college.

As it currently exists, the OntarioLearn model is well-suited to expanding course options for students already enroled in a college program and could be expanded for new short programs or micro-credentials for working-age lifelong learners.

The Open Universities Australia model

Established in 1993, OUA is governed as a standalone non-profit organization with seven shareholders, all of which are Australian universities. This shared governance encourages greater partnership and integration between institutions and a robust quality assurance framework.

To clearly delineate the relationship between OUA and each of the institutes in the consortium, a detailed provider agreement is negotiated. These agreements include everything from details about the release date of course material to the division of tuition fees. The registration process is integrated so that provider institutions are immediately notified when a student enrols in one of their courses through the OUA. Tuition fees are divided between the provider institution to cover the cost of delivering the course, and OUA to cover administrative costs. Also included in the provider agreements are clear guidelines for quality assurance, credit transfer and intellectual property rights.

From the student perspective, OUA is a one-stop-shop. While courses are delivered through consortium institutions, enrolment, tuition payment, and access to most support services are through OUA. Student advisors can assist with issues of financial assistance or registration, and they have access to a student’s academic record at all provider institutions enabling them to provide academic counselling. There is also a 24/7 telephone counselling service, a full career services department, and online academic skill-building modules. This full-service approach sets the OUA model apart from other consortium approaches such as OntarioLearn.

8. Partner with government on workforce development programming

The pandemic-induced global recession and the associated spike in unemployment and job displacement has focused attention on the role of government-funded workforce programs in rapid retraining and upskilling. Employment services, traditionally geared towards job search and immediate labour market attachment, are being redesigned to focus on more holistic approaches to career and workforce development.[106] Through a post-secondary lens, Canadian higher education entrepreneur and reformer Ryan Craig describes the need for “full-stack solutions that directly overcome the key barriers keeping both job seekers and employers from bridging the education-to-employment gap.”[107]

The Ontario government’s ambitious redesign of the employment and training system, launched in 2019, is piloting a new model in three regions of the province.[108] As part of a long-term integration of multiple siloed employment programs, each pilot region has one competitively-selected Service System Manager (SSM) accountable for all service provision and coordination in that region. Funding for the SSMs is determined both by operational needs and performance outcomes. Representing a substantial transformation of the current system, aspects of the government’s approach have been criticized — particularly the similarity to recent reforms in Australia that have not lived up to expectations.[109]

With the selection of Fleming College as the SSM for Muskoka-Kawarthas region, the Employment Ontario transformation also offers a compelling test case for partnership between higher education institutions and public workforce programming. Fleming already operates two employment services locations, and the college believes the SSM opportunity aligns with its focus on “providing learners with skills aligned with labour market needs to ensure broader and sustainable employment in our communities.”[110] Specific details about the Fleming SSM model are not yet available, but the pilot, which runs to 2022, could lead to new opportunities for symbiotic integration of the college system with employment services and workforce development programs across Ontario.

Lessons Learned: What can be applied in Ontario?

Institutions should identify the learners they can best serve along the skills continuum. Among the Ontario examples, Fleming College is expanding in workforce development; Ontario Tech Talent is focused on upskilling for current undergraduate students, graduates and employer partners; WLU is introducing specialized short-programs in high demand fields; and Ryerson is using continuing education to serve learners with postsecondary degrees. There is a different path for every post-secondary institution to serve working-age lifelong learners.

Program design should respond to learner needs. Institutions such as WGU and SNHU that have been most successful in attracting working-age learners at scale have committed to wholesale change of organizational, program and learning models to reflect learner needs, through substantial investment in marketing and recruitment, skills- or competency-based education, fully online program delivery, and substantial efforts to enhance flexibility and supports for students.

In choosing a model, institutions should build on their strengths and capabilities. From Penn State World Campus’ efforts to build within existing academic structures to Ryerson’s focus on continuing education and ASU’s bespoke corporate partnerships, institutions have taken different approaches based on their own context, culture and objectives. The choice of model reflects the institution’s capacity for change and innovation; where there is less existing capacity, or where there will be strong resistance from faculty and other key stakeholders, institutions have turned to new structures and external partnerships.

Private providers offer significant potential benefits but also risks. The assessment of OPM partnerships has been decidedly mixed. In some cases, including WLU, the private partner enabled the successful launch of a program the institution could not have. In others, such as University of Florida Online, overly ambitious growth targets, poorly structured contracts, or other factors have resulted in failure and damage to the institution’s brand. OPMs should be viewed as neither a panacea nor a sellout of higher education, but as a new tool in the toolbox. They require a focus on high quality learning experiences, strong graduate outcomes, appropriate sharing of risk and revenues, and reasonable expectations on growth and scaling.

Partnerships with other institutions, employers and local partners hold promise and reduce risk. Examples such as the OntarioLearn consortium show that formal partnerships with other institutions, with employers, or even with the government can and do work in the Ontario context. Given the geographic distribution of Ontario institutions, bespoke partnerships with local or regional employers likely hold significant potential. Even in the absence of formal agreements, understanding the demands in local labour markets requires strong partnerships and a commitment to community and industry engagement.

4. A Playbook for Presidents and Policymakers

After assessing the changing higher education landscape in Ontario, the emerging marketplace for lifelong learning globally and in the province, and the array of new institutional approaches to serve working-age learners, this section offers practical guidance for higher education leaders and administrators, as well as for policymakers at Queen’s Park.

First, we apply a strategic lens from the vantage point of public universities and colleges, considering potential objectives and value propositions, self-assessment of institutions’ strategy and capacity for innovation and change, and other considerations in choosing a new model for serving lifelong learners (i.e. the learners, organization and governance, program design, and financial model).

Second, for provincial policymakers, we propose principles that could underpin a lifelong learning agenda, and specific enablers through public policy and funding arrangements that could help catalyze change.

In both cases, we believe the implications and recovery demands of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis for higher education will act as a powerful accelerant.

A Three-Step Approach for Higher Education Leaders

All Ontario post-secondary institutions operate within a common provincial marketplace, policy and regulatory environment, and grant funding, tuition and student aid frameworks. Yet each university and college is also unique and differentiated: across missions and strategic priorities, operational and financial circumstances, local and regional community dynamics and needs, enrolment demand and student profiles, and other factors.

Put differently, interest in the pivot to serving working-age learners will be heavily influenced by institutional characteristics and context. For example, large comprehensive universities, focused on research prestige or graduate and professional education (medicine, law, engineering), may see less incentive. By contrast, colleges, having five decades of experience with a variety of more vocational education and training, may feel they already serve this population well. Mid-sized universities and polytechnics looking to differentiate, innovate or build profile and prestige may see a compelling case. Small, northern and other non-GTA institutions may be looking to deepen engagement with their local community and industry, or to use virtual learning to entice distant learners. In general, institutions facing financial viability challenges could see greater opportunity. Those with more ambitious leadership teams might as well.

The lifelong learning opportunity will consequently resonate very differently at different institutions and there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach. This section offers a set of steps institutions can take in considering whether and how to proceed.

Identify your institution’s objectives and value propositions

The first step is to consider your institution’s objectives in contemplating a pivot to new or adapted programs for working-age lifelong learners. There will surely be a range of perspectives among the institutions’ various decision-makers and stakeholders: presidents and leadership teams, boards and governing councils, faculty and administration staff, and current students and community. There are compelling value propositions that could mobilize support for action, such as:

- Leveraging your public mission and brand to deliver higher quality educational options and greater value for working-age students, through a commitment to better learning, completion and career outcomes than they could achieve through private competitors.

- Growing and diversifying your revenues as part of a sustainable financial model by pursuing enrolment

- growth through a large new market of adult learners – in your community and potentially beyond.

- Offering new programs and learning models — with features like enhanced online delivery, skills or competency-focused curriculum, stackable micro-credentials, or enhanced student supports — that offer positive spillovers to current programs and students.

- Presenting a compelling, differentiated impact narrative for government funders and policymakers, industry and community partners, and working learners by positioning your school at the leading edge of a workforce transformation.

Ruthlessly assess your institution’s strategy, context and capacity for change

If expansion into lifelong learning is indeed an objective and the value proposition for your university or college is clear, the next step is an uncompromising assessment of your institution’s strategic, organizational and financial context, and the conditions for success in advancing a significant change initiative. We offer five key questions to consider, though there are surely others.

First, what is the level of urgency for change and program innovation at your institution? If a university or college is already facing financial sustainability issues, long-term pressures or short-term shocks to enrolments, demands for program renewal, or pressures from local and regional stakeholders for responsiveness to economic and workforce needs, there should be more urgency and appetite for ambition.

Second, what learners are you best equipped to serve? If the institution is in a weak competitive position versus other providers with existing learner markets (e.g. 18-22 year old undergraduates, apprentices in skilled trades training, research-focused graduate learners, highly-skilled executive MBAs), pivoting more aggressively to programs for underserved working-age adult learners could offer greater benefits.

Third, can the institution remain viable within its local or regional market, or does it need to attract students from beyond its community? While the attraction of GTA and international students have been a lifeline for demographically challenged colleges and universities in smaller and northern communities, U.S. universities like Western Governors offer examples of highly scalable growth through fully online, remote-learning models.

Fourth, what partnership potential exists in introducing new programs? Geographic location, local labour market characteristics and institutional program focus will likely inform the assessment of potential partnerships with industry and employers, industry groups, or other education and training or workforce development providers in the community. Other program development partners, in education technology or online program development, will not be geography-bound.

Fifth, what level of change and innovation will the institution be open to? Launching programs for working learners likely requires significant changes to the traditional higher education business process, from admissions and curriculum to program delivery and learner supports. An honest appraisal of the institution’s internal capacity and culture—including the administration’s appetite for change, the labour structure and state of faculty relations, the likely response from the institution’s governance bodies—will reveal whether changes to core academic programs, or other in-house options, offer much chance of success.

Those proposing bold new initiatives must be prepared to engage with the critiques that are commonly leveled by opponents: that lifelong learning is a “cash grab” and a distraction from the core mission; that education is much more than serving the needs of industry; or that high quality standards can be difficult to establish in non-traditional program models.

Consider which type of model would work best for your institution

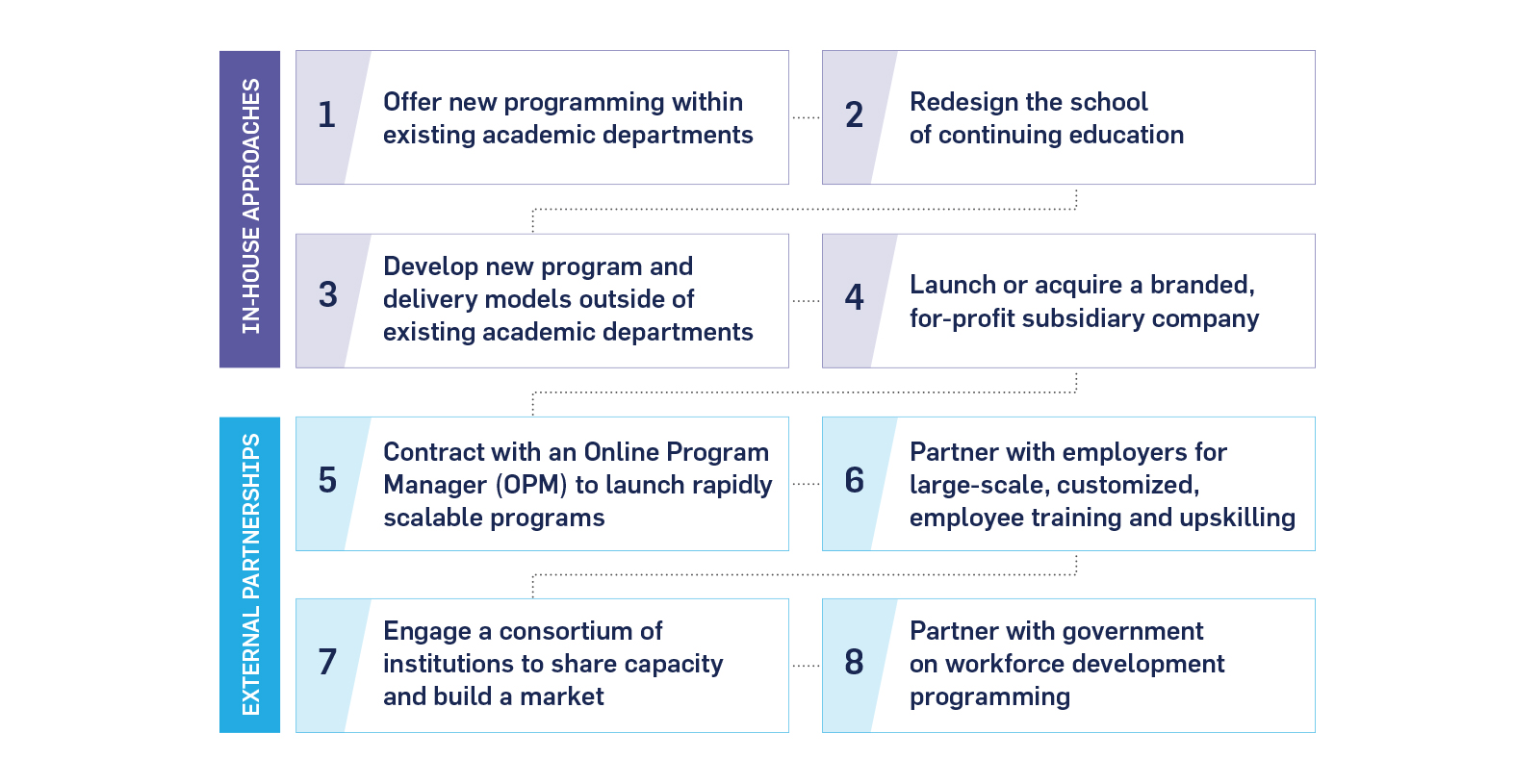

Section three presented a scan of the higher education landscape for emerging models to serve working-age lifelong learners, including case examples from Ontario and other jurisdictions south of the border and elsewhere in the world. While it was not exhaustive, it presented eight institutional and system approaches, grouped as either “home grown” within institutions or achieved through “external partnerships.” They are recapped here.

The section concluded with a set of lessons learned regarding the relevance and applicability of these models for Ontario’s colleges and universities. While they need not be repeated here, a key insight is that institutions can pick and choose among the models and their various features to identify an approach that works best for them. As higher education leaders consider lifelong learning model types and program design for their institution, there are a set of standard factors to consider:

- The target adult learners to whom your program will cater: What segment are you aiming for in the education and skills continuum — from vocational training and upskilling for lower-skill, more barriered learners; to courses and micro-certificates in emerging and in-demand sectors; to advanced credentials geared to learners in high-skill industries? Your assessment of institutional strategy, focus and competitive position should inform this decision.

- The program structure to serve your target learners: The profile and needs of the working learners you aim to serve should guide the program design and learning models. Key design factors include the fields of study, and their link to employer demand or WIL opportunities; the delivery model, from in-class to fully online and hybrid or blended; the form of credential, and whether programs will offer academic credit; how prior-learning and skills should be recognized; and the flexibility and supports you can offer, around start-dates and self-pacing, learning pathways, career planning and mentorship, and other student services.

- The organizational model and governance arrangements: Based on your assessment of institutional strategy, capacity and change-readiness, what approach stands the best chance of success — whether expanding within existing academic departments, continuing-education schools, through new corporate entities or partnerships, or hybrid options? Each raises different governance questions (e.g. buy-in and approval through leadership teams, boards and senates; the role of faculty and staff, and their unions; contractual terms and arrangements with partners; or government funding and approvals).

- The financial model that can ensure your program is viable: Your goals for any new program will include financial sustainability at minimum, and more likely net positive revenues to the institution. As section three’s case examples reveal, this is achievable but not assured. Revenue models typically focus on up-front fees, though income share agreements, government grants, bespoke employer partnerships or other potential sources exist. Students financial aid, through OSAP, Employment Ontario or the new Canada Training Benefit, could bolster access, but eligibility varies by learner and by program (see policy section below). On the expense side, startup costs and ongoing delivery expenses will vary depending on program structure and scale. Models like OPM revenue-share partnerships, though bearing risks, are attractive to institutions that lack financial or organizational capacity to quickly bring a new program to market.

The “Policy Brief” for Queen’s Park Policymakers

Just as there are compelling reasons for institutions to expand their offerings for working-age lifelong learners, there is a strong case for the provincial government to use the policy and fiscal levers at its disposal to support and encourage institutions to innovate. This section lays out a set of principles and proposals for Ontario policymakers to advance a lifelong learning agenda.

Principles to guide a provincial lifelong learning agenda

The Government of Ontario is well-positioned to advance a lifelong learning agenda as part of a broader strategy for higher education and the province’s workforce. At a systems level, the Strategic Mandate Agreements (SMAs) and expanded performance-based funding model are important levers for establishing provincial objectives and financial incentives, formalized through institution-by-institution plans. These reforms, combined with the Employment Ontario transformation, can enable greater alignment between the higher education and workforce systems over the medium- and long-term. Targeted investments, such as recent funding commitments for micro-credentials and COVID recovery re-employment programs, offer short-term carrots to institutions, employers and employment service providers.

At the same time, Ontario continues to lack clearly defined goals for reform in the higher education system, much less an articulated strategy and policy agenda for stewarding change. The SMAs and funding reforms, while promising stewardship levers, have been criticized for lacking clear and ambitious objectives, failing to adequately address data collection shortfalls, and for introducing faulty performance metrics, among other things.[111] Other reforms, such as to student assistance and tuition frameworks, similarly lack coherence without anchoring within a broader strategy. A vision for lifelong learning should be part of this strategy, either as a standalone objective or as part of more detailed goals and metrics in areas already identified as government priorities, including labour market alignment and community impact.

Moving from vision to policy, the following set of broad principles would inform a clear government agenda for expansion of lifelong learning:

- Quality, value and outcomes for learners; through recognition of prior learning, high standards for programs and pedagogy, focus on completions and career outcomes, and transparency around program and credential value in the job market.

- Demand-driven differentiation for institutions; pursuing comparative strengths in learner segments, program design, and fields of study, where there is demonstrated labour market demand.

- Permissive higher education policy to maximize room for innovation; through clear, outcome-oriented system goals, frameworks and metrics, rather than prescriptive requirements, processes, and input-oriented performance measures.

- A competitive lifelong learning marketplace for public and private providers; with public funding primarily following the learner so they can choose their learning pathway and find the institution that best supports them, and a greater emphasis on employer investment reflecting sizable private benefits.

- Cooperation among public universities and colleges both to lay the foundations for rapid acceptance of new credentials through the development of common definitions and standards, and to compete as one united system in an increasingly national and global online learning marketplace.

- Sustainable, diversified finances for institutions; with policy and funding levers encouraging smart growth, innovation, and new revenue sources from the lifelong learning market.